comunitat

3. Community

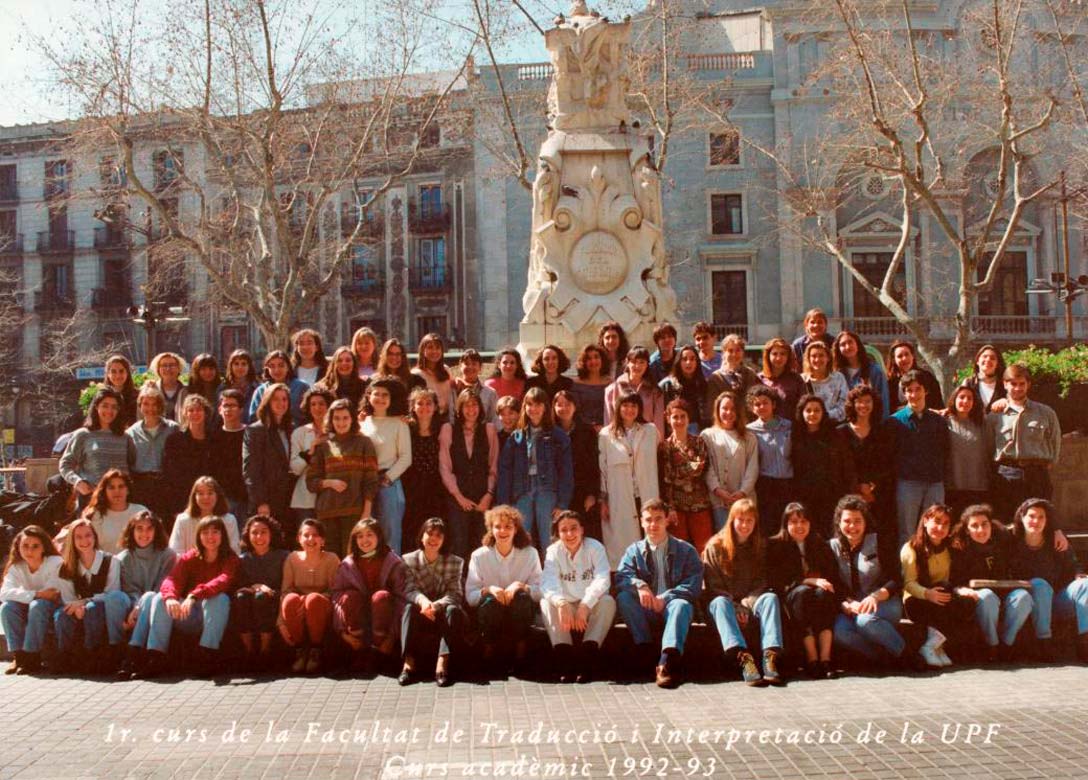

The shrinking gap between languages and technology: thirty years of changes at the UPF Faculty of Translation and Language Sciences

How has the work of translation and linguistics professionals changed in recent decades in the wake of the widespread growth of the Internet, digital technologies and the audiovisual industry? As part of the 30th anniversary of the UPF Faculty of Translation and Language Sciences, we take a look at how these university studies have evolved since 1992. Amongst other things, career opportunities and lines of research have become more diverse, with new applications in education, healthcare and even automatic text generation through the use of artificial intelligence.

What does it take to work in translation, interpreting or linguistics today? What fields can languages be applied in? A closer examination of UPF’s Faculty of Translation and Language Sciences shows that future professionals in these industries are increasingly trained in the use of technological tools and statistics, so they can work with the vast volumes of data afforded by the Internet, as well as in the fields of terminology and linguistics. It also shows how these disciplines contribute to the development of artificial intelligence (AI) applications that reproduce natural language, the detection of cognitive disorders involving speech impairments, the increased accessibility of web content, and the search for more effective methodologies for classroom language teaching.

One need only look to this faculty, which turns 30 this year, to grasp the major transformations the sector has undergone in recent decades. The faculty has managed to adapt to these changes, whilst at the same time preserving the essence of its original project and of the curriculum first launched in the 1992-1993 academic year.

Esteve Clua, lecturer at the faculty since 1992: ‘From the start, it was understood that translators or interpreters are cultural mediators’

Esteve Clua, a lecturer at the UPF Faculty of Translation and Language Sciences since it first opened its doors who will only this year be retiring, summarized the essential features of that curriculum, which are largely still in place today. On the one hand, it was based on the conviction that students needed to have a good command of the target language, i.e. the language a text will be translated into (in UPF’s linguistic context, Catalan or Spanish). On the other, the aim was for students to specialize in a small number of source languages (i.e. the original language of a text), so they could study them in depth. Initially, the first and most intensively studied language was English, which students could combine with a second foreign language: French or German.

The original curriculum already reflected the need to combine training in literary translation with training in many other fields of translation, such as legal or financial translation, where there is a greater demand for professionals. Additionally, ‘It was understood from the start that translators and interpreters are cultural mediators’, said Clua. ‘Students thus also had to be trained in the cultures of the communities that speak the source language.’ All of this was related to another curricular requirement: students had to spend at least one term abroad in a country in which the source language was spoken, not only to improve their knowledge of the language itself, but also to immerse themselves in its culture.

The University of Geneva: the European benchmark for the first curriculum

When it came to designing this first curriculum, UPF looked to foreign models. There were few other references at the time in Spain. Although some thirty universities in the country offer such studies today, in the early 1990s, only three were doing so before UPF: the Autonomous University of Barcelona, the University of Granada and the University of Las Palmas de Gran Canaria.

Specifically, UPF drew inspiration from the Geneva School of Translation and Interpreting (today, a Faculty), the best in Europe, where Albert Ribas, now a professor emeritus at the Swiss university, worked. Clua considers Ribas the ‘father of the idea’ for the faculty’s first curriculum. According to Ribas himself, ‘After a series of exploratory visits to other higher schools of translation and interpreting, UPF’s first rector, Enric Argullol, concluded that the Geneva School of Translation and Interpreting, where I worked at the time, was the most suitable model for UPF’s founding goals. As a result, beginning in 1990, academic and administrative ties were established to develop a coherent pedagogical project.’

In addition to Ribas, who would go on to become a lecturer at the new faculty, and Clua himself, other co-founders of the UPF faculty included Teresa Cabré, María Paz Battaner, Jenny Brumme, Mercè Tricàs, Antoni Badia and Maite Turell.

Eduardo Mendoza and Isabel Clara Simó taught at the faculty in the 1990s

Although the Faculty of Translation and Language Sciences is currently located on UPF’s Poblenou campus, which opened in 2009, in the early years, classes were held at the university’s former headquarters, on Barcelona’s Ramblas. Even once teaching had begun in the classrooms, essential challenges remained to be tackled to more firmly establish the new studies.

The university’s Department of Translation and Philology (which, since the 2008-2009 academic year, has been called the Department of Translation and Language Sciences) did not even exist yet. It was not created until 1996; once it was, one of its main initial objectives was to consolidate the teaching staff, which was still in its infancy. The number of teachers gradually grew, coming to include renowned figures, such as Eduardo Mendoza, Isabel Clara Simó, Feliu Formosa or Ángel Crespo, who mostly collaborated as adjunct lecturers. This first stage also saw the creation of the department’s first research groups, with the help of various Spanish and European grants, as well as the launch of doctoral studies. By the late 1990s, the teaching and research staff were already some 100 people strong, a figure that has only continued to grow in the interim and that, today, stands at almost 150, including the adjunct lecturers. The vast majority (65%) are women, as is still commonplace in many humanistic disciplines.

Teaching and research staff by gender

As the faculty grew, ‘it also needed a larger administrative structure’, explained Montse Coll, a member of the university’s administrative and service staff. Since 1993, she has done administrative work related to the teaching of these studies in the various UPF units and services to which this responsibility has fallen over the years. Coll recalls both periods of intense work in those early years, when everything still remained to be done, and other more light-hearted moments, when she and her administrative and service staff colleagues teamed up to celebrate special events, such as Carnival or Christmas, decorating the office or organizing recreational activities. These celebrations, which have become more subdued over time, also helped establish a good working environment at the newborn faculty, which would later also promote various cooperation projects, beyond the strictly academic sphere. One good example of this was the project to improve the quality of language teaching in Senegal, run by a team of teachers from the faculty for fourteen years (2007-2021), in which the first head of the Department of Translation and Philology, Mercè Tricàs, was involved.

From one long degree programme to three bachelor’s degree programmes: a growing teaching offer

Propelled by the drive of its founding team, the faculty was able to continue expanding its activity. Initially, it offered only a single long degree programme in Translation and Interpreting, which, in the 2008-2009 academic year, was converted into a university bachelor’s degree programme in order to bring it into line with the European Higher Education Area (EHEA). Today, the faculty also offers two more bachelor’s programmes, one in Applied Languages and the other, a double bachelor’s degree programme in Translation and Interpreting and Applied Languages.

The very profile of the teaching and research staff that joined the faculty over the years is what ultimately enabled it, well into the 21st century, to expand its academic offer. ‘Long before that, we already needed people with expertise in the various fields in which a translator has to be trained: the translation process, knowledge of the foreign language, aspects of linguistics such as morphology, semantics and pragmatics, not to mention literary studies, cultural mediation, etc. Later, we capitalized on that critical mass of researchers to launch new studies’, said Anna Espunya, current head of the Department of Translation and Language Sciences.

The rise of the Internet paves the way for an increased focus on technology in the faculty

The vast majority of disciplines studied and researched in the field of translation and language have been impacted by the rise of digital technologies, especially since the dot-com boom at the turn of the 20th century. One of the clearest examples of this is machine translation, which can save time and effort, although it cannot be used with all kinds of texts and, in any case, must always be post-edited by a professional. ‘Literary translation’, for example, ‘requires a manual, artisanal process’, said Marta Marfany, a lecturer at the faculty and expert in the field, as in these cases, the professional plays an essential role as a cultural, historical or linguistic mediator. This is why, in the first and second years of the bachelor’s programmes, ‘students are taught to translate more manually; it is not until the third year that they are trained in post-editing’, added the current faculty dean Carme Bach.

However, the applications of technology in the field of linguistics go well beyond machine translation. Researchers can use it to automate repetitive operations, store information, solve complex tasks, etc. More and more researchers are also looking at linguistic applications in the field of AI, for example, for automatic text generation. The current overlap on UPF’s Poblenou campus of the Faculty of Translation and Language Sciences, the Department of Information and Communication Technologies (DTIC), which brings together various branches of engineering, and the Department of Communication, which offers Audiovisual Communication, Journalism, and Advertising and Public Relations programmes, helps foster mutual synergies in interdisciplinary fields of study.

Marta García, a fifth-year student on the double bachelor’s degree programme in Translation and Interpreting and Applied Languages, believes it is important to train in the use of technology and plans to further her studies in the field of computational linguistics. ‘I will continue my training with a master’s degree to specialize in linguistics, probably oriented towards the branch of computational syntax, morphology and semantics.’

The growing diversification of career opportunities and research fields in translation

Some of the faculty’s graduates have gone on to play very prominent professional roles in the field. Ariadna Font, for instance, was director of Twitter’s Machine-Learning Platform until Elon Musk’s takeover of the company and has also led several projects at IBM. Her case exemplifies the diversification of the fields of application of linguistics, not only because of its interrelationship with technology, but also the growth of multimedia formats. The proliferation of television channels and pay-per-view platforms and the boom and diversification of the world of gaming also offer myriad opportunities to professionals in the sector, who can work in dubbing or subtitling in film or television.

Veteran professionals in the translation industry have had to adapt and learn to live with these changes. For example, Scheherezade Surià, who has been a practicing translator for nearly two decades, earned her degree in Translation and Interpreting at UPF from 2000 to 2004 and also holds several master’s and postgraduate degrees. To date, she has combined literary translation with financial, legal and corporate translation and has also dipped her toes into the audiovisual industry. For instance, from 2009 to 2010, she did translations for animated films such as Madagascar or Shrek. ‘Although I translate more books than films, it’s true that there are a lot of opportunities in audiovisual translation right now due to the emergence of so many audiovisual platforms in recent years: Netflix, HBO, Amazon Prime, etc.’

At the turn of the 21st century, the faculty changed its curriculum for the first time and launched a second-cycle degree in Linguistics

The spread of digital technologies and multimedia channels and the growing internationalization and convergence with Europe are some of the factors that have had the greatest impact on the successive changes in the faculty’s curricula. The first changes were made to the curriculum at the start of the 21st century, to update it and ensure its sustainability. Additionally, in the 2003-2004 academic year, a second-cycle degree in Linguistics was launched, for people who had already completed a first-cycle – or full – degree in another discipline. The second-cycle programme allowed them to complement their studies with training in linguistics and acquire knowledge and skills related to technological applications in the field.

From a long degree to a bachelor’s degree: adapting to the European Higher Education Area (EHEA)

In those years, the faculty also undertook the challenge of adapting to the European Higher Education Area (EHEA), following the 1999 Bologna Declaration. In the 2005-2006 academic year, it participated in a pilot project of the Catalan government for EHEA adaptation that was implemented in five degree programmes at UPF, including the degree in Translation and Interpreting. As part of this pilot project, the faculty offered a three-year UPF-specific bachelor’s degree in Linguistic Mediation. Initially, the Catalan government sought to converge with the most widespread model in the EU today (three-year bachelor’s degrees and two-year master’s degrees) rather than the system ultimately adopted in Spain to adapt to the EHEA framework (four-year bachelor’s degrees and one-year master’s degrees). This degree was offered for three consecutive academic years.

UPF: the only university in Spain to include sign language in its Translation and Interpreting studies

The bachelor’s degree in Translation and Interpreting was adapted to the four-year model, which was launched at UPF in the 2008-2009 academic year. It had many points in common with the earlier long degree programme, but also some significant differences, as its launch coincided with a change in the curriculum. One of the most important differences was undoubtedly the inclusion of Catalan Sign Language (LCS from the Catalan) in the bachelor’s degree studies. UPF thus became the first university in Spain to incorporate sign language into its Translation and Language Sciences studies, enabling students to choose to train as interpreters of this language, in addition to English, French or German. (see the highlight on this topic)

Since 2008, students have also been trained in two languages with the same level of specialization (English and French, German or Catalan Sign Language). They have also been trained to translate into both Catalan and Spanish. Another new feature was the inclusion of social communication and audiovisual media subjects in the academic curriculum.

The faculty then leveraged the momentum from this thorough renewal of the curriculum to continue to expand its activities and teaching offer. Just one year later, it launched its second bachelor’s degree programme, in Applied Languages, offering advanced training in the possible applications of linguistics in professional, institutional, business, educational and sociocultural contexts or computerized environments, for example, in tasks such as post-editing, the linguistic revision of printed or digital texts, or linguistic and cultural mediation in public services (schools, health centres, courts, etc.), amongst others. The design of the faculty’s second bachelor’s programme drew on its experience with the previously launched second-cycle programme in Linguistics.

Since the faculty began to offer the two bachelor’s programmes, another trend has begun to emerge: students interested in pursuing both types of studies at once. According to Bach, this is what prompted the creation of the double bachelor’s degree programme in Translation and Interpreting and Applied Languages, with a total duration of five years (one year more than the other two bachelor’s programmes).

Marta García, student on the double bachelor’s degree programme in Translation and Applied Languages: ‘I am very interested in translation, but I also wanted to study other language-related disciplines, such as linguistics or language teaching’

Marta García, a fifth-year student on the double bachelor’s degree programme who is specializing in English and German, explained why she chose to pursue these studies at UPF. ‘I was very interested in translation, but I also wanted to study other language-related disciplines, such as linguistics or language teaching.’ She also recalled everything she got, both personally and academically, out of her time abroad at King’s College in London during the first term of her second year.

This offer of three different degree programmes and the requirement for students to spend at least one term abroad are some of the main features that set the UPF Faculty of Translation and Language Sciences apart from those of other universities, said Bach. According to Espunya, UPF also offers more specialization credits in German, French and specialized translation (legal, financial, scientific, etc.).

The option of studying a third language: Russian and Chinese make their debut at the faculty

Currently, the university also offers students the option of starting a third language, such as Russian or Chinese, although not to train to the level required to translate or interpret in it, as in the cases of English, French, German or Catalan Sign Language. The option was launched in 2019 for students starting with a level C1 or higher in one of their two languages of specialization (which in English, for example, would be equivalent to the Cambridge Advanced Exam, or CAE).

At the same time, the faculty has rolled out EDvolution, the UPF education model, created in 2018 to promote more active learning methodologies. According to Dean Bach, the very characteristics of the Translation and Language Sciences studies, which had historically already included a highly practical dimension in addition to the theoretical training, facilitated the faculty’s adaptation to UPF’s new education model.

Increasingly more options for further education and research once students have earned their bachelor’s degree

Today, as part of the bachelor’s degree studies, interested students may also take a number of optional research subjects, where they can get their first taste of this field. The range of options available to students to continue their education or research after earning their bachelor’s degree has multiplied since the faculty first opened its doors. In the 1990s, the University Institute of Applied Linguistics (IULA), founded by the renowned philologist Teresa Cabré, brought together much of the research in linguistics. Since the first calls for applications under the Catalan government’s research group support programme (SGR), the department has gradually built a stable map of research groups in disciplines related to translation and language sciences. (more information in the highlight on this topic)

Irene Latorre, a trainee researcher and member of one of these groups, TRADILEX (Translation, Discourse and Lexicography Research Group), explained how she came to conduct research on this topic. ‘Discourses are a tool of power and social change and I have always wanted to know all about what shapes them in order to understand everything around me. In a world where information is consumed instantaneously, it is key to try to get down to the truth of what is being spread.’

Latorre joined this research group after earning her master’s degree in Discourse Studies, one of five official master’s degrees coordinated by the Department of Translation and Language Sciences offered only by UPF, in addition to its master’s programmes in Translation Studies, Theoretical and Applied Linguistics, Translation between Global Languages (Chinese-Spanish), and Teacher Training for Secondary Education, Vocational Training and Language Teaching.

The Department also has a Doctoral Programme in Translation and Language Sciences and participates in two official master’s degree programmes coordinated by other universities, in Cognitive Science and Language and in Training for Teachers of Spanish as a Foreign Language. Additionally, the Institute for Applied Languages, which is part of the Department, offers several online postgraduate courses on terminology.

Translation and Language Sciences studies, in figures

Evolution of the number of students by academic year

Translation and Language Sciences studies today (academic year 2022-2023)

Students by gender

Students by degree type

Between its bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral studies, the faculty currently has 996 students, twice as many as in the late 1990s. The vast majority (80%) are women.

Breakdown of undergraduate students

Esteve Clua, lecturer: ‘Today, there are more students born in Catalonia but to parents of foreign origin. This is an opportunity to accentuate our students’ profiles as mediators.’

The increased number of courses offered and growing volume of students has also made the administrative tasks required for teaching more complex, explained Coll, who works in the Translation and Language Sciences Administrative Management Unit (UGA from the Catalan), which is currently staffed by a team of 14 people. However, digital technologies have streamlined many of the management processes, she said. ‘These days, students are more technologically savvy. They do more things online and come in less.’ This trend has grown even more pronounced since the Covid pandemic and its associated shelter-in-place periods.

According to Coll, ‘there are more international students today’ than when she first joined the faculty in the early 1990s, especially in the master’s programmes, where international students currently account for 62.61% of the total. In contrast, Bach pointed out, most undergraduate students are still national, although there is a growing trend in this group, too. As Clua explained, ‘Today, there are more students born in Catalonia but to parents of foreign origin. This is an opportunity to accentuate our students’ profile as mediators.’

What drives the faculty’s current students?

In a globalized society, the faculty’s current student body is quite heterogeneous, in terms not only of their origins and cultural traditions, but also their reasons for choosing these studies. Espunya offered a few examples of what motivates students today. ‘We get people who are good at foreign languages, people interested in literary translation; people with a pragmatic mindset with a view to the professional world. In the Applied Languages programme, we get more people interested in going into education, into language teaching.’ In her view, the faculty also needs to be able to attract more students with a ‘mathematical mindset’. ‘Part of language sciences falls within the cognitive and technological sciences. We would like to get people with scientific and technological interests’, she said.

In addition to attracting a diverse student body, with a more hybrid profile that combines humanistic and scientific-technological aspects, encouraging interest in pursuing careers in translation and linguistics remains a challenge for UPF and for all universities that offer these studies.

To this end, UPF organizes several prizes and contests, especially aimed at secondary school students. For instance, it awards prizes for the best research work in the fields of languages and linguistics, including one specifically for Catalan Sign Language. The faculty also holds a translation contest for lower and upper secondary school students and hosts the Batxibac conference, which helps raise awareness of this academic pathway, which allows students to work towards Catalan and French secondary school qualifications (batxillerat and baccalauréat, respectively) at the same time. Other prizes include the Talent Awards, given to the students with the best academic transcripts to enrol in Translation and Language Science studies at UPF. Furthermore, to mark the faculty’s 30th anniversary, several commemorative events and roundtables on the past, present and future of the sector are being held this academic year.

Nine out of 10 students find jobs

Surià, a freelance translator, encourages young people interested in translation and linguistics to train and pursue a career in the industry. ‘Although many newly minted translation graduates join the market each year, the field is so broad and rich that it is very feasible to break in’, she said. Still, she warned, it is necessary to fight for better working conditions for translation professionals. According to data from the Catalan University Quality Assurance Agency (AQU) from 2020, the employment rate for people who had graduated four years earlier from the UPF Faculty of Translation and Language Sciences (89.9%) was higher than the average for all the university’s studies (86.6%), but the average monthly salary was lower (1,725 euros vs an average of 2,194 euros). It is also an industry in which many professionals choose to be self-employed (16.4% vs 6.2% on average amongst all UPF bachelor’s degree alumni).

Although getting started is always tough, translation and language sciences are a field that today has more social applications and career opportunities than in the early 1990s. Whilst technology has partially automated translation, the work of professionals in post-editing and, especially, mediation cannot yet be done by machines, especially in the field of literature or poetry. At the same time, the hybridization of the humanities and technology has opened up new interdisciplinary professional and research fields that combine linguistics, computer science and artificial intelligence. Where will these new lines of work and research lead? We will have to write at least another thirty years of the faculty’s history to find out.

Timeline

-

The UPF Faculty of Translation and Interpreting opens its doors.

-

Creation of the University Institute for Applied Linguistics (IULA), founded by the renowned philologist Teresa Cabré. The pre-existing Neology Observatory (OBNEO) is incorporated into the IULA.

-

Creation of the UPF Department of Translation and Philology.

-

Launch of the second-cycle degree course in linguistics (no longer offered), for people from other studies seeking to train in this field.

First edition of the postgraduate course Expert in Catalan Sign Language Interpreting, a joint initiative of UPF and the Catalan Federation of Deaf People (FESOCA). -

The Faculty participates in a pilot programme of the Catalan government to adapt Catalan university studies to the European Higher Education Area (EHEA): a new three-year degree programme in Linguistic Mediation is launched at UPF and offered for three academic years.

-

Second edition of the postgraduate course Expert in Catalan Sign Language Interpreting.

-

Reform of the curriculum, entailing several changes, including a new requirement for Translation and Interpreting students to train in two languages with the same level of specialization.

Launch of the EHEA-adapted bachelor’s degree programme in Translation and Interpreting, which replaces the former five-year degree programme.

Inclusion of Catalan Sign Language (LSC) in the bachelor’s degree programme in Translation and Interpreting.

Department’s name is changed. Since the academic year 2008-2009, it has been called the Department of Translation and Language Sciences.

UPF hosts the 13th edition of the International Congress of the European Association for Lexicography.

-

Launch of the bachelor’s degree in Applied Languages.

Launch of the Barcelona Summer School on Bilingualism and Multilingualism, which has been held every two years since, offering a comprehensive view of the state of the art of bilingualism and multilingualism research.

-

The 27th edition of the European Summer School in Language, Logic and Information, the leading European summer school on the study of meaning, is held at UPF.

-

Start of the double bachelor’s degree programme in Translation and Interpreting and Applied Languages.

-

Creation of the LSC-UPF Actua Centre for Catalan Sign Language Studies to promote research projects and educational and social outreach activities related to LSC, amongst other things.

-

The Faculty adds Russian and Chinese, making it possible for students with a level C1 or higher in one of their two strong languages of specialization to acquire knowledge of a third.

-

The 29th edition of Europe’s leading computational linguistics congress, the International Conference on Computational Linguistics, is held on the Poblenou campus. It is co-organized by the Department of Translation and Language Sciences and the Department of Information and Communication Technologies (DTIC).

-

The 7th edition of the International Association for Translation and Intercultural Studies Conference (2021) is held at UPF.

-

The Faculty celebrates its 30th anniversary with a series of commemorative activities held throughout the 2022-2023 academic year.

How have translation and language sciences studies changed in the last thirty years?

Carme Bach, dean of the faculty

‘The way translation is done has changed, as have translation needs. Today, more specialized translation is required. In our increasingly intercultural society, the fields of applied languages have also changed and grown.’

Anna Espunya, head of the department

‘We usually attract students who are interested in languages. But part of language sciences falls within the cognitive sciences and technologies. We would like to get people with scientific and mathematical skills and knowledge, too.’

Marcel Ortín, lecturer at the faculty since 1994

‘At first, the teaching was mainly oriented towards practical training for translators and multilingual writers. Over time, the elements of reflection on translation and, also, on languages have been strengthened, and the specific bachelor’s programme in Applied Languages was created. Now it’s time to think about the inevitable consequences, for future teaching, of the improvements being made in machine translation and AI tools.’

Scheherezade Surià, faculty alumna and translator

‘Although I translate more books than films, it’s true that there are a lot of career opportunities in audiovisual translation right now due to the emergence of so many audiovisual platforms in recent years.’

Irene Latorre, researcher in TRADILEX (Translation, Discourse and Lexicography Research Group)

‘Good use of the technological applications that are now available can not only considerably facilitate our work as researchers, but also help enrich our studies. These applications can show us certain patterns within discourses that can be very useful.’

Montse Coll, administrative and service staff member

‘We have adapted to the new ways of working, with more students each academic year in the bachelor’s and master’s degree programmes, some of them international; we have learnt new things and grown with the faculty.’

The evolution of translation and language sciences studies from four perspectives

Video with the testimonies of Esteve Clua, professor at the Faculty since its origins in 1992; Marta Marfany, professor at the Faculty since 2009; Scheherezade Surià, translator and UPF alumni (class of 2004); and Marta García, double degree student in Translation and Interpretation and Applied Languages.

Looking back at the faculty

Memories of former deans*

-

Núria Bouza,** (1993): ‘As vice-rector for Academic Planning and Teaching Staff, I helped coordinate the process of developing the faculty’s first curriculum by delegation of the rector.’

-

María Paz Battaner (1993-1999): ‘Although it already had humanities studies, UPF wanted a faculty with language and linguistics studies. Attention to languages is a knowledge need for all universities. At the time, it looked to the Geneva School of Translation and Interpreting as a model. That school was very effectively turning out experts in applied languages to meet the high demand there was for such professionals in Swiss society.’

-

Pilar Estelrich (1999-2004): ‘In that stage, we promoted internationalization by hosting exchange students, via the Internet and, even more so, through the implementation of online work or international cooperation.’

-

Luis Pejenaute (2004-2010): ‘The guiding principles of the bachelor’s degree in Translation and Interpreting, launched in 2008, were a firm commitment to multilingualism and mediation; the inclusion of Catalan Sign Language as another language; the offer of several subjects related to social communication and audiovisual media; and the possibility of studying two specializations.’

-

Cristina Gelpí (2010-2013): ‘UPF is the only Spanish university to offer a global project in the field of sign language, specifically, Catalan Sign Language (LSC), the natural language of signing deaf and deaf-blind people in Catalonia. From the start, UPF has had a strategic interest in the field of LSC as it occupies a unique place both in teaching and research and as a community social commitment.’

-

Maria Dolors Cañada (2013-2016): ‘We noticed that many Translation and Interpreting student were choosing Applied Languages subjects as optional subjects and vice versa. The double bachelor’s degree programme, which has a limited number of places, enabled students to train in both fields: with just one more year of study, they would multiply their career opportunities.’

-

Sergi Torner (2016-2021): ‘The professional practice of translation – and, in general, of all disciplines linked to language sciences – has been profoundly altered by the evolution of technologies linked to language-data processing and artificial intelligence [...]. The new professional profiles increasingly point towards specialized proofreading and post-editing jobs.’

Memories of former department heads*

-

Mercè Tricàs (1996-2000): ‘Those of us who were part of the initial management team of what is now the Department of Translation and Language Sciences and who helped paved the way for the path it has travelled view with pride its dynamism and the remarkable progress it has made in research and teaching over these nearly thirty years of history.’

-

Antoni Badia (2000-2005): ‘One important milestone in those years was the launch of the second-cycle degree programme in Linguistics, with a computer science orientation. As in so many other fields, the possibilities that language technologies offer language professionals are enormous.’

-

Enric Vallduví (2005-2011): ‘In Poblenou and the 22@ district, there is a better fit with the urban and institutional environment. And the co-existence with the engineering studies and research groups, as well as the communication studies – with which we had already shared the Rambla building – has been enriching. The technical infrastructure is good and everyone falls in love with Plaça Gutenberg!’

-

Àlex Alsina (2011-2018): ‘The pressure to internationalize has not been detrimental to our own languages: students who earn one of our faculty’s bachelor’s degrees must have comparable commands of Catalan and Spanish; they also have the option of studying Catalan Sign Language.’

*All the aforementioned people provided information and data used for this story.

**Núria Bouza, a full professor of Private International Law, was part of the first rector’s office team at UPF. In 1993, she briefly served as acting dean, at the request of UPF’s first rector, Enric Argullol, until the philologist María Paz Battaner took over this responsibility. Before Bouza, the faculty’s first dean, from 1992 to 1993, was Amalia Rodríguez.