“The Indigenous Struggle for the Environment in Latin America” Report of the eleventh Policy Dialogues session

“The Indigenous Struggle for the Environment in Latin America” Report of the eleventh Policy Dialogues session

“The Indigenous Struggle for the Environment in Latin America” Report of the eleventh Policy Dialogues session

“We have to create in this world a global society that promotes social justice, that promotes climate justice and that promotes racial justice. Because without any one of the three, there's not going to be justice in the world.”

Indigenous communities in Latin America are at the forefront of the fight for environmental and climate justice. They face multiple threats to their lands, health, cultures and livelihoods, caused by climate change, large-scale industrial projects by transnational corporations, and a lack of political representation. Deforestation, primarily caused by industrial agriculture, the extraction of fossil fuels, and mining, for example, represent attacks on the territories and rights of indigenous communities. Even the “green transition” towards renewable energies in order to slow down the climate emergency has provoked an unprecedented increase in extractivist projects in Latin America. Faced with these violations of their individual and collective rights, and the increase in natural disasters caused by global warming, indigenous communities and leaders across Latin America are mobilising to protect their territories and the environment. Nevertheless, their voices and struggles are often silenced in mainstream media and politics.

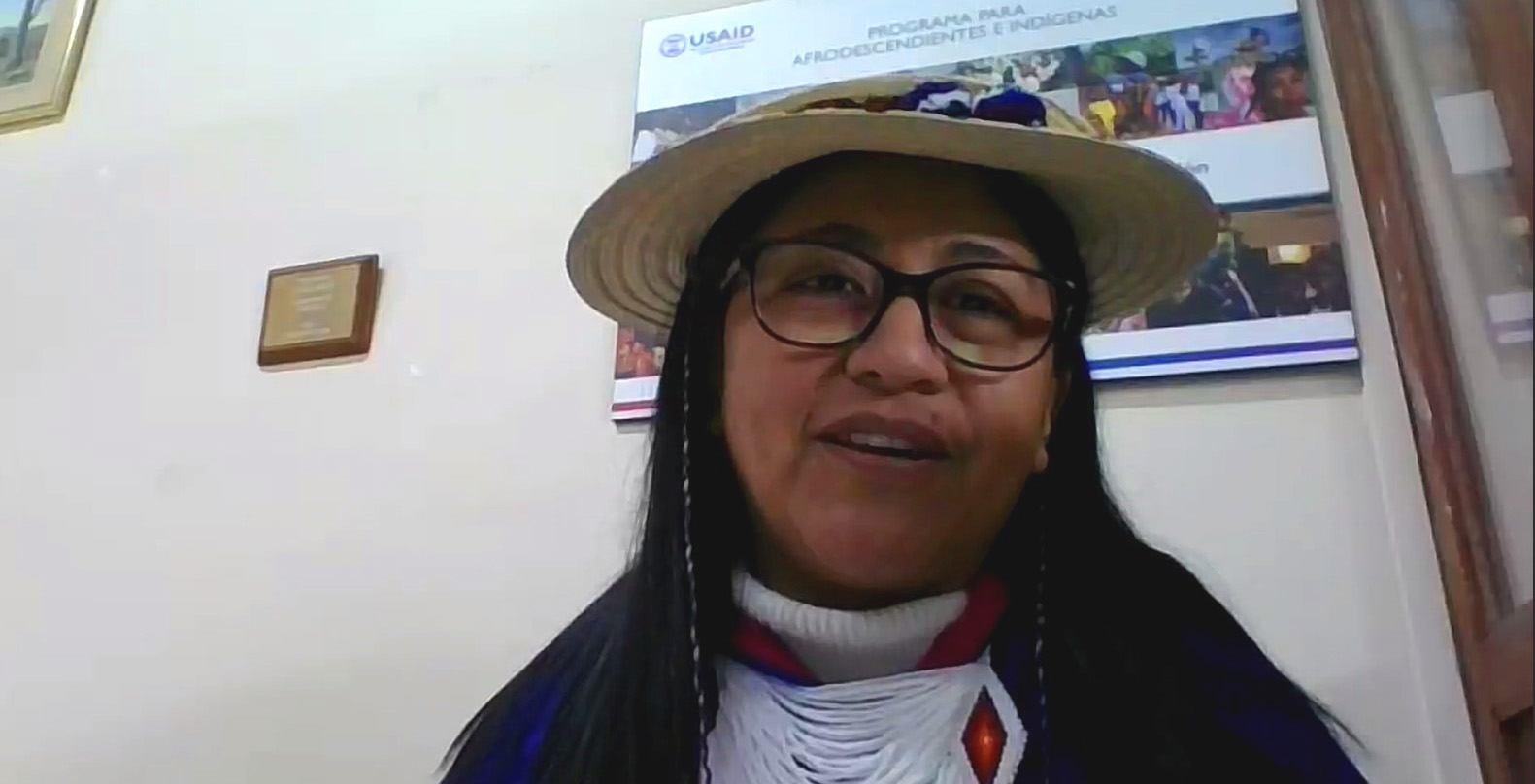

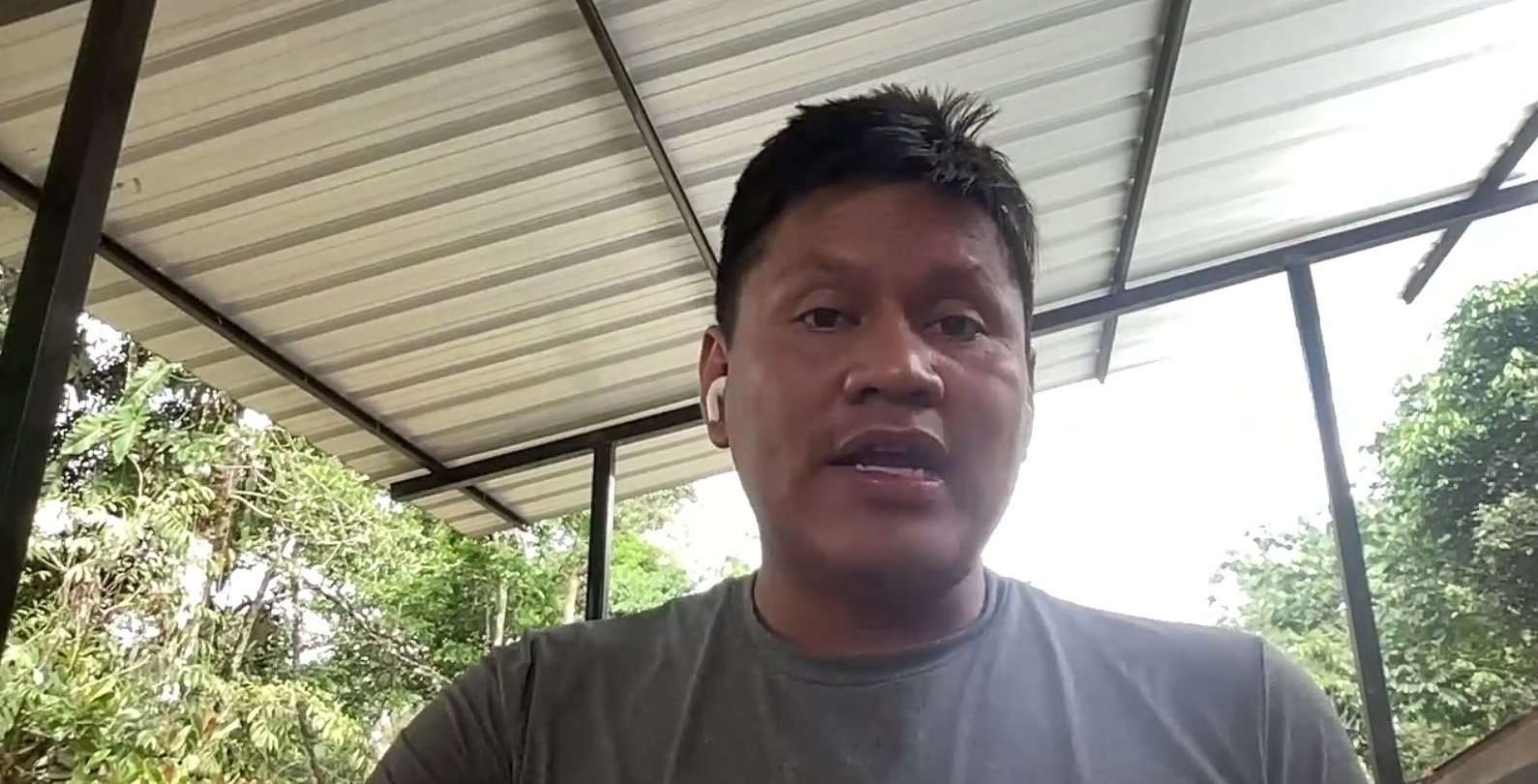

In order to increase understanding and recognition of these mobilisations, the JHU-UPF Public Policy Center delivered the eleventh Policy Dialogues session on the topic of “The Indigenous Struggle for the Environment in Latin America”. The speakers were Mamá Mercedes Tunubalá Velasco (from the Misak community, Colombia, and the first indigenous woman to become Mayor of a municipality in Colombia) and Leonardo Leonel Cerda Tapuy (young Kichwa activist from the Serena community in Ecuador, founder of the Black and Indigenous Liberation Movement (BILM) and Executive and Founder of the Hakhu Amazon Foundation). The session was moderated by Beatriz Rodríguez-Labajos, Beatriu de Pinós researcher on environmental justice movements and artivism at the JHU-UPF Public Policy Center.

Leonardo started the session with the following statement regarding indigenous activism: “We, indigenous people, whether we want to or not, are connected to processes of struggle, processes of defence, and processes of existence of the indigenous people…because since the colonisation process, indigenous peoples have always been connected to processes of existence, resistance, protection and struggle for access to basic services.” He went on to explain how indigenous communities in Ecuador are denied access to basic services such as clean water, education, housing and electricity, and therefore people living in these situations “don’t have any other option but to resist and fight for [their] rights and the rights of the collective.” He explained how the communities in his region of Ecuador are suffering the environmental and health impacts of hydroelectric dams, oil extraction projects and mines. A major issue is the contamination of the rivers by gold mines: since 2020, the Ecuadorian state has given over 148 new concessions for gold mines in the Napo province. The local indigenous communities depend on these rivers for their life: “if our water is contaminated it is a certain death for us and our families”.

Leonardo also described the dichotomy that young indigenous people face in the 21st Century: they have grown up in ancestral cultures that see humans not as the centre of the world, but as one element of it, existing in an intimate relation that humans have with the territory. However, these cultures have been stripped of their rights in a colonised, capitalist world that doesn’t value their people or the environment. Therefore, the challenge is to understand which tools of the current day they can employ for the defence and protection of their territories and to work towards a post-extractivist future. He advocated the need to build collective solidarity economies that are not based in an extractivist mentality but in indigenous thought and knowledge, and which aim to maintain the balance of life on earth. Leonardo spoke of the “Sí al Yasunì” campaign to protect a biosphere in Ecuador from industrial projects which would extract the oil from its earth. The campaign has pushed for a national referendum regarding the future of the biosphere, which will take place on the 20th August 2023. The event is of international significance as it will be the first time that a national referendum is being held to take a decision regarding a post-extractivist future.

During Mercedes’ interventions, she described the “planes de vida” (plans for life) that the indigenous communities in Colombia have been developing and working to incorporate in the country’s legislation and policies. The indigenous planes de vida are long-term plans based on core principles and values that come from ancestral indigenous knowledge. They represent an alternative approach to governance and policymaking; one which respects all living beings and manifests the indigenous philosophy of “Buen Vivir” (loosely translatable to “living well”). She explained how indigenous communities, and particularly women, started to critique the development model of capitalism from this perspective: “Capitalism gives signals of crisis…where few are happy and the aim is not saving life but development and money.” This model, where human life is valued in statistics and numbers and nature is commodified for profit, is not compatible with the indigenous worldview and planes de vida as it does not manifest respect for all life or harmony with nature. As an economist and mayor, Mercedes promotes the need to evaluate economic models and public policies according to the values and principles of Buen Vivir. Ultimately, the question is whether they harm or protect life on earth, which contrasts with the capitalist model of development. She stated, “the improvement of living conditions of human beings is not guided by the economic growth of goods and products.”

Mercedes discussed how the indigenous perspective and principles can be integrated in the mainstream political institutions of Colombia. She referred to the importance of the 1991 constitution, which recognised for the first time the rights of the country’s indigenous peoples. Since this development, indigenous communities have more political participation and recognition in Colombia, and are using this to promote and implement their planes de vida, which include questions of education, housing, environment, etc. Mercedes recognised that “nothing will change if we only see things from an institutional perspective”. Nevertheless, she expressed hope in the current government of Colombia and its potential to increase the protections and rights of both nature and indigenous peoples.

Both speakers coincided in that systemic change is necessary to tackle the climate crisis and protect the rights of indigenous communities in Latin America. They also agreed on the need for indigenous peoples to be active and have autonomy, particularly in the management of their own resources, funds and institutions: “we are not going to ask the violator how to stop violating. It’s not like that. That is why we have to organise”, said Leonardo. He gave the example that since the 1970s, less than 7% of the global funds for helping indigenous peoples actually reached their communities: the rest was spent on things such as consultancies, third sector organisations and foreign NGOS that didn’t improve the conditions of indigenous communities.

During the discussion, the speakers were asked a question regarding the national debt of Latin American countries. In response, both Mercedes and Leonardo pointed out that in reality, it is the “developed” countries that are indebted to Latin American countries, for the resources and wealth they have stolen and extracted from them and the damage they have done to the environment and communities since the start of colonisation. Furthermore, they indicated the need to avoid new kinds of externally-implemented “green” policies that could constitute new forms of colonisation of indigenous peoples.

Leonardo Leonel Cerda Tapuy (young Kichwa activist from the Serena community in Ecuador, founder of the Black and Indigenous Liberation Movement (BILM) and Executive and Founder of the Hakhu Amazon Foundation).

Follow us on Twitter to hear about our upcoming Policy Dialogues seminars @pubpolcenter and our Instagram account @publicpolicycenter