Auditory stimuli may be a good marker for early diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease

Segons un treball publicat a Scientific Reports, per Manuela Ruzzoli, investigadora del Centre de Cognició i Cervell i primera autora de l'article, que explora la fiabilitat de l'estímul sonor com a possible marcador de demència.

The evidence suggests that Alzheimer’s disease is part of a continuum, characterized by long pre-clinical phases that precede the onset of the symptoms of the disease. In several cases, this continuum begins with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), in which daily activities are preserved despite the presence of certain cognitive impairment, mostly through aspects of memory.

The possibility of having a reliable and sensitive neurophysiological marker that could be used for early detection of Alzheimer’s disease would be an extremely valuable diagnostic tool in a highly prevalent disease. A study published in September in Scientific Reports, sought to find the reliability of auditory mismatch negativity (aMMN) as a marker capable of identifying the progression of mild cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. A study by Manuela Ruzzoli, first author of the paper and researcher at the Center for Brain and Cognition (CBC) of the Department of Information and Communication Technologies (DTIC) at UPF, in collaboration with Italian researchers at the University of Trento and the San Giovanni di Dio Centre in Brescia.

Auditory mismatch negativity or aMMN is a component of the brain’s electrical activity that responds to auditory stimuli and can be highlighted via a simple electroencephalogram (EEG). It is used as an index of sensory and attention memory. This type of experiments involve the production of a series of regular or standard sound stimuli that suddenly become different or anomalous. These stimuli generate brain waves that can be captured via an EEG.

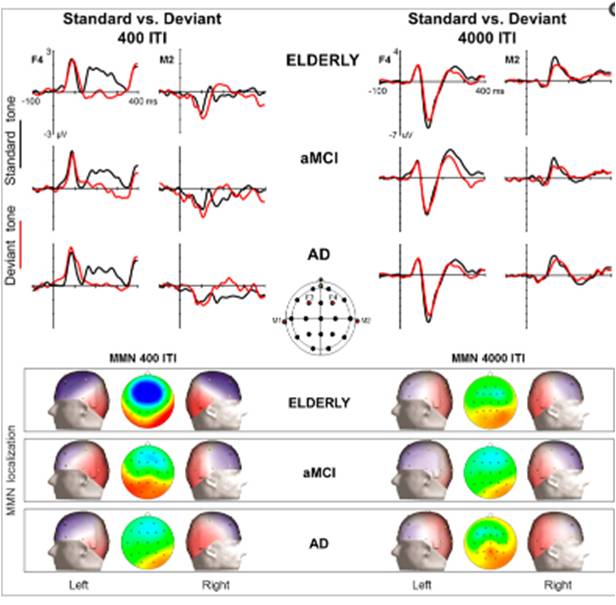

As Ruzzoli explains: “Our study evaluated the potential alterations of the sensory auditory memory in patients with dementia and mild cognitive impairment, compared with a control group of healthy elderly people. To identify possible differences between the three groups in the coding of acoustic stimuli and/or maintenance of the representation of these stimuli over time, the brainwaves of EEG recordings caused by a series of regular, auditory stimuli interrupted by less frequent (anomalous) auditory stimuli presented at short and long time intervals were compared”.

As Ruzzoli explains: “Our study evaluated the potential alterations of the sensory auditory memory in patients with dementia and mild cognitive impairment, compared with a control group of healthy elderly people. To identify possible differences between the three groups in the coding of acoustic stimuli and/or maintenance of the representation of these stimuli over time, the brainwaves of EEG recordings caused by a series of regular, auditory stimuli interrupted by less frequent (anomalous) auditory stimuli presented at short and long time intervals were compared”.

This experiment had to be crucial to identify patients with Alzheimer’s disease able to respond to short but not long intervals of stimulus, due to the impairment of their sensory memory. Similarly, patients with mild cognitive impairment should be halfway between normal ageing and dementia. Thus, the authors wanted to be able to distinguish between normal and pathological ageing, in its early stages.

So, in this study the researchers compared the aMMN values of the three study groups: 18 healthy elderly people; 12 people with mild cognitive impairment, and 19 diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease. The values of aMMN were obtained in different brain locations, frontal and temporal, through a series of regular auditory stimuli interrupted by less frequent (anomalous) auditory stimuli presented at short (400 milliseconds) and long (4000 milliseconds) intermediate intervals.

Results of the experiment with sound stimuli

The results of the experiment showed that faced with an anomalous sound of short duration and intermediate interval, people with mild cognitive impairment responded to stimulation in its temporal location, while people with Alzheimer’s disease did so in their frontal zone. The healthy senior citizens responded to the same type of auditory stimulus in both parts of the brain. However, when the intervals between the stimuli administered was long, the response only was only obtained in the group of normally ageing subjects, and more specifically in the temporal lobe.

Hence, the study concludes that aMMN could be used as a marker to distinguish between normal or pathological ageing with regard to age-related cognitive neuropsychological impairment. “The interesting thing about this marker is that it is not intrusive, it can be obtained passively (without the person or the patient paying direct attention), it is an easy marker to record and calculate and it does not require very much technical or computational specialization”, added Ruzzoli.

In short, aMMN could be introduced at clinical centres, in routine clinical practice, to assess solidly and reliably whether it could be a method to diagnose cognitive impairment in people inherent in Alzheimer’s disease, already in its early manifestations.

Reference work:

Manuela Ruzzoli, Cornelia Pirulli, Veronica Mazza, Carlo Miniussi, Debora Brignani (2016), “The mismatch negativity as an index of cognitive decline for the early detection of Alzheimer’s disease”, Scientific Reports, 12 September, DOI: 10.1038/srep33167.