How will AI coexist with human music? The future is now

How will AI coexist with human music? The future is now

Article by Karma Peiró*

Imagine a world where the next hit song is written not by a human songwriter but by a machine. That future could already be the present. Following rapid advances in artificial intelligence and other new technologies, the Music Technology Group at Pompeu Fabra University has led a project to analyze the changes in how music is created, distributed and listened to.

Computer-composed music is not new: the first such compositions date back to the late 1950’s. But when in 2017, the British rock band MUSE generated a video for their new single "Dig Down" using the latest in artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning capabilities, the response from fans was huge. The tool used by the band scoured the internet to find hundreds of hours of footage of celebrities, politicians and artists. These clips were then "sewn" together using time cues from the original song, with each lyric spoken by a different person.

"AI is so often deployed in very invisible ways, so it was exciting to work with the band on a project that brought them to the forefront”, reported Branger Briz, the tech development agency who collaborated with the band. "We think it's important to have a public discourse about the promises and perils of these emerging and incredibly influential technologies".

Just two years later, the cross-border pop group YACHT went even further. The band set themselves the biggest challenge of their seventeen-year career by inviting AI into their creative process. "We wanted to find a way to question technology more deeply," explained lead singer Claire L. Evans. Evans and her bandmates –Jona Bechtolt and Rob Kieswetter– hand-selected their favorite AI compositions and then arranged them into the songs that make up the successful Grammy nominated album Chain Tripping. "We didn't really know anything about what was possible with artificial intelligence. We only knew that it had to somehow go beyond generative ambient music", argued Evans in a talk for Google.

To produce it, the band first tried to unearth any existing YACHT formulas by collaborating with engineers and creative technologists and exploring their own back catalogue of 82 songs using machine learning tools. Melodies, lyrics, artwork and videos were created by the intelligent system. “This record is a product of a technological moment that is rapidly evolving. We didn’t set out to produce algorithmically-generated music that could ‘pass’ as human. It taught us everything we wanted to know about ourselves: how we work, what moves us, and which ambiguities are worth leaning into”, explained Evans.

The entire process was captured in the documentary The Computer Accent (released in 2022), which documents the research, composition and recording and allows the viewer to experience the band´s fears and amazement at the potential capabilities of current AI. Making this album gave rise to questions about their own role in a future where software anticipates, generates and even synthesizes human work, as well as the relevant ethical issues of the moment.

Both examples, from MUSE and YACHT, will already be out of date by the time you read this article. As mentioned at the outset: computer-composed music is nothing new, but the difference today is that soon, thanks to AI, it may be possible to create the next hit song without any prior musical knowledge or skill. Anyone could do it. So, will AI be an ally for musical creativity? Can machine-generated music have the same effect on listeners as music made by humans? How quickly will the industry embrace this innovation and how quickly will we embrace it? What ethical questions arise from this revolution? As yet, there are no concrete answers.

Technology moves at the speed of light. At least that is what it feels like. And we are not slowing down, but rather flying at super speed towards an unknown destination. We’re on a jumbo jet, up in the clouds, with no clear view ahead, few clues as to where we’ll end up and many questions without answers. Fasten your seat belts! We may be in for a bumpy ride.

Gathering all voices

Artificial intelligence is the star among technologies in the creative field today. Last year we were all excited and open-mouthed at systems that generate images from text descriptions, like Dall-E, Midjourney or Stable Diffusion. It was logical to assume that music-related innovation might be next.

In the last quarter of 2022, the Music Technology Group (MTG) at Pompeu Fabra University launched the Challenges and Opportunities in music tech project to identify how AI and other new technologies are changing the processes of creating, distributing, learning and listening to music.

In order to develop solutions to support a fair and transparent digital transformation of the sector, it is crucial to understand the needs and concerns of all relevant stakeholders. Since 1994, the MTG has carried out research at an international level on topics such as audio signal processing, music information retrieval, musical interfaces, and computational musicology. Its main goal is to contribute to the improvement of the information and communication technologies related to sound and music, and at the same time communicate its findings to wider society."The concept of open science is fundamental in academia, and that means we are keen to avoid being siloed. For years, we have made great efforts to be more accessible, and this project is going in that direction", explains Xavier Serra, director of MTG.

With this goal in mind, from September to December of 2022, they held an open discussion between the key stakeholders in music: industry executives, creators, listeners, music students, archivists, developers, etc. to analyze the challenges and opportunities for the music sector, but also the significant impact AI is likely to have on society and culture. "This change will have implications for everyone, not just the musicians of the industry. So we thought it was important to also hear the silent voices involved in this technological shift", Serra added.

“How are AI and other new technologies changing the processes of creating, distributing, learning and listening to music ?”

Through various formats - surveys, in-depth interviews and a face-to-face event with the audience- they spent four months gathering thoughts, reflections, concerns and future aspirations of the music sector in relation to artificial intelligence and other emergent technologies such as blockchain and metaverse. This article reflects the discussions, suggestions and feedback of one hundred contributors, from both the international and local music sector, who are committed to the creativity, listening, education and archiving of the music we all consume today.

“Machine learnings”

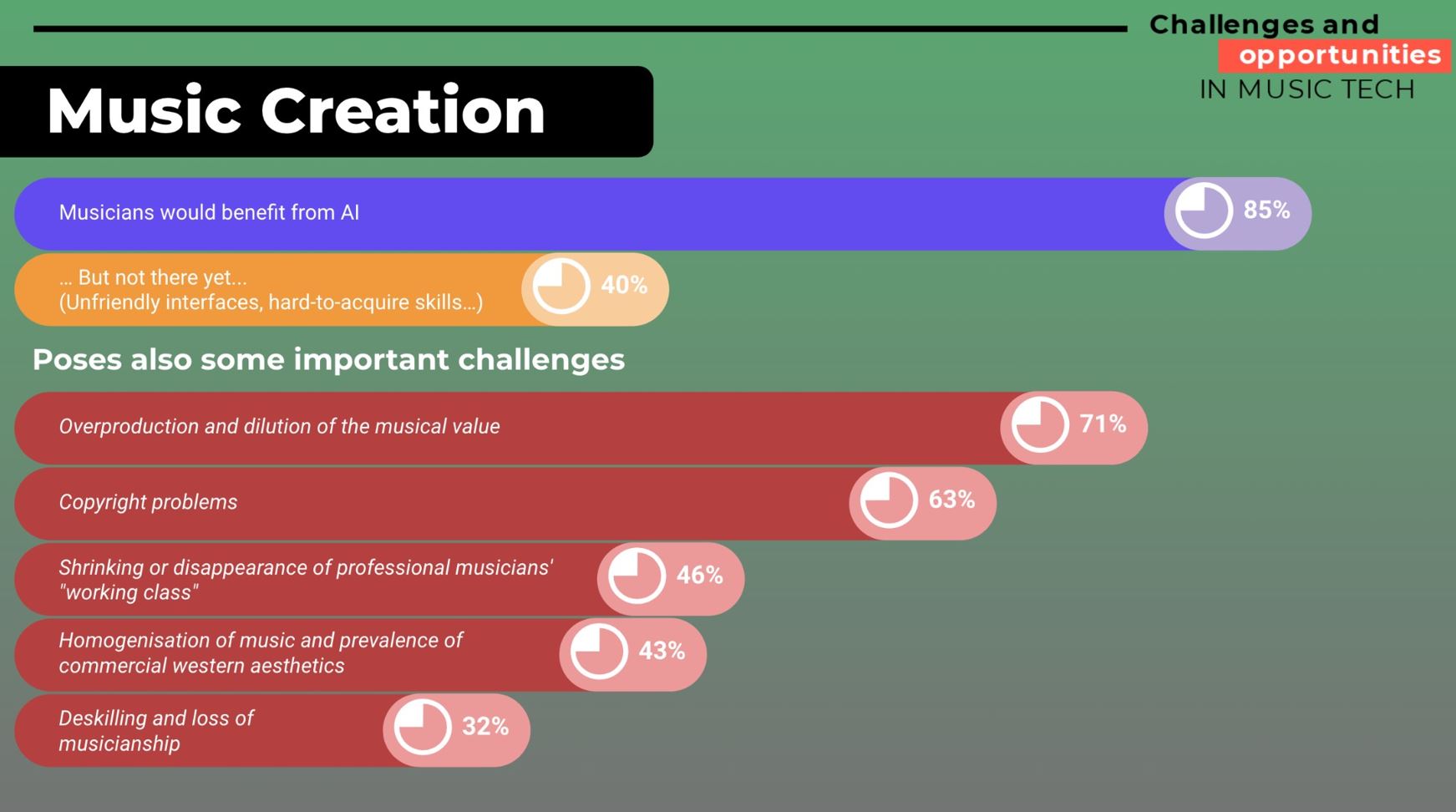

One of the main conclusions of the MTG project is that musicians will ‘undoubtedly benefit from AI very soon’. AI could help musicians with a whole range of tasks: composition, synthesis, sample browsing, mixing and mastering. However, some respondents of the surveys identified “problems with unfriendly interfaces, hard-to-acquire skills or simply unconvincing results”.

The solution might come from Google. In January 2023, the tech company’s latest AI tool made its debut simplifying what seemed to be an inconvenience for the sector. The system can generate music, of any genre, based on a text description. The paper "MusicLM: Generating music from text" describes how the algorithm was trained with a dataset of 280,000 hours of music to generate minute-long pieces from text prompts or descriptions. For those who do not relish a 3 or 4 year music degree or time-consuming technical training, all this new tool needs is a short instruction, such as: "Crate a smooth jazz melody with a catchy saxophone solo and a solo singer" or "90s Berlin techno with a low bass and a strong kick".

Can this machine make music as creatively as that made by humans? If so, it could become an inspiration, a companion, the perfect solution to writer's block. But if the machine compositions meet with the listeners approval, will AI be in competition with musicians?

"Musicians will undoubtedly benefit from AI in tasks such as composition, synthesis, sample browsing, mixing and mastering"

The current situation also brings other challenges arising from the relationship with new technologies. 71% of the survey participants in the MTG project believe that AI could lead to overproduction and a dilution of musical value. On the latter point, it's a fact that the economic aspect of music creation is already being watered down. The study "Music creators earnings in the digital era", published by the UK Intellectual Property Office in 2021, confirms these fears. This ground-breaking study concludes that only those artists who achieve around one million streams per month in the UK over an extended period can make a living from music. “In the UK, that's just 0.4% of the musicians on streaming platforms” says the report.

Cutting out the intermediaries?

In the context of these considerations, other concerns emerge related to the technological disruption we are currently experiencing. For example, the reduction or disappearance of many professional musicians. What will happen with the studio session singers that –among others–will be affected by AI?. Functional music –such as that which can be heard in restaurants, spas, lifts etc, and often goes unremarked by its intended audience– can nowadays be composed by machines. It seems this job may be disappearing as a human activity. It makes sense: what company would be willing to pay an anonymous professional when it can get hundreds or thousands of hours of royalty-free “muzak” for a subscription fee?

The homogenisation and the prevalence of commercial Western musical aesthetics is another threat to be faced. What is, as yet, unclear is whether AI music will just make more of the same, plowing the same old furrow of global pop tropes, or whether it will have the capacity to unearth new sonic gems, discover uncharted musical territories and create new genres that no musician has yet explored.

“We address a peer-to-peer world where all the relationships among creators and fans relate directly”

In addition to AI, other technologies such as blockchain/NFTs or metaverse point to a possible transformation of the music sector, but still contain many unknowns. Blockchain promises to eliminate the intermediaries, but before this becomes a reality, the question is whether the industry will allow it. "Blockchain will bring clarity to the current problems of legal rights for artists. It is a great technology that focuses primarily on creators and audiences," said Marcelo Estrella, an intellectual property advisor at Across Legal, who specializes in legal tech and innovation. "It facilitates the process of recording transactions and tracking assets in a business network. For artists, it will allow them to have a comprehensive peer-to-peer database that will store detailed information about music copyright and intellectual property. This would help artists to be credited for their creative work”, he added.

“Immutable, transparent, public and inalterable” are some of the qualifications used by supporters of blockchain to assert that this technology is bound to be applied in the near future. “Also we have the advantage of NFTs as vehicles, a direct link between creators and audiences”–, maintains Marcelo Estrella,- “that will lead to the inevitable elimination of the intermediaries. We address a peer-to-peer world where all the relations among creators and fans relate directly. This will have a strong impact on society, like the instant payments through the smart contracts; or data that audiences can provide to creators”.

Human-in-the loop, yes or no?

No one disputes the fact that current AI tools have enormous potential, and it is already predicted that new sounds and rhythms will be discovered and new genres invented through human-machine interaction. Today's intelligent systems can create music at a speed that was unimaginable until recently. But will AI displace the music creator and will listeners become loyal fans of songs produced exclusively by machines?

“For me, if humans are out of the loop, it is going to be a sad future”, says Rob Clouth, a multidisciplinary artist working in the fields of electronic music, computational sonics and new media. “I think that there will always be artisan musicians that appreciate the process of creation. To me, part of making music is thinking about what other people will like”.

The music curator Antonia Folguera has a different view: “As a listener, I wouldn't mind if my next favorite song is made by AI”, she says. “If it's good enough, why not? But it would be a bit boring because I would want to know more about who is behind that song. And if I found that the author is a software program, I would get bored pretty fast”. However, Folguera confesses that when performing as a DJ, there are many occasions in which she is searching for a specific beat or sound and in that context, being able to use AI would be a massive bonus. She also feels ok about removing the burden from humans of having to create what is known as “elevator music”.

The experimental electronic music producer and Senior lecturer in Music Audio Technology at De Montfort University (UK) Anna Xambó, argues: “Why not think outside the box and follow the ideas of the researcher Nick Collins about considering an autonomous system without human-in-the-loop? We are at the beginning of the journey”. Along these lines, this years’ Ai Music Generation Challenge 2023, which in past years had focused on generating compositions in different musical traditions, is indeed focused on creating a new artificial music “tradition”.

Doubts are only natural

At this point, the debate drifts into unavoidable ethical questions, as we know in advance that there is no certain answer or solution. If we use artificial intelligence to create something, who should be considered the owner of that work? The programmers of the model? The authors of the training dataset? The trainer, the curator, the musician behind it? The company that owns the model or tool? The AI itself? Should we still attribute authorship to anyone? What do the current laws say about this? If we have not yet achieved fair remuneration for musicians, how will we resolve this technological ambiguity that combs through millions of sounds to create something completely different?

Everyone consulted for the MTG project agrees that this is a difficult question and one that we will be discussing for a long time to come.

All of the latest awe-inspiring AI systems –such as Dall-e and others–, give us results after mixing millions of images, sounds and texts without ever crediting a human creator, and offer no impetus for users to go in deeper and explore further the work of the original artists, writers, scientists or researchers. If these tools are used on a large scale, will we be increasingly dependent on their output without having the chance to explore our past in a different way?

"Perhaps we should think about coral ownership, accept a multiplicity of authors, skip the romantic figure of the composer”

Artist Rob Clouth suggests a solution: "Dall-e could display the ten most similar images in the dataset with links to the authors' websites. That has more to do with reference, rather than ownership, but it's something".

The lawyer Marcelo Estrella recalls the scenario in Europe today. EU copyright law provides for AI creations to be classified as "works". So unless you can prove that the AI creation falls into one of these scenarios, it is directly part of the public domain:

- Step one: The AI-assisted output must be a production in the literary, scientific or artistic field

- Step two: The AI-assisted output must be the result of human intellectual effort

- Step three: The AI-assisted output must be original.

- Step four: The work must be identifiable with sufficient precision and objectivity.

Public domain means that no individual owns the work; rather, it is owned by the public. Anyone can use a piece of work in the public domain without obtaining permission and without citing the original author, but no one can ever own it. Of course, these possible scenarios are based on European legal principles. The situation is different in other parts of the world. A white paper authored by Eric Sunray, the legal intern at the Music Publishers Association and a specialist at the American University Washington College of Law, argues that “AI music generators violate music copyright by creating tapestries of coherent audio from the works they ingest in training, thereby infringing the United States Copyright Act’s reproduction right”.

“Life vest under your seat”

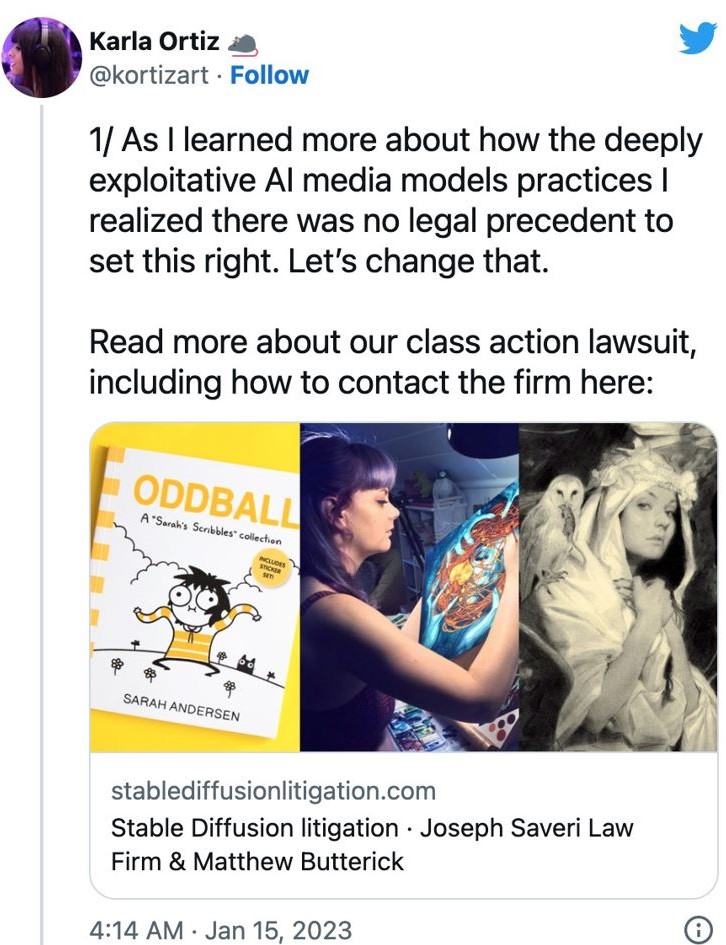

The ethical debate was sparked when, in January this year, a trio of artists –Sarah Andersen, Kelly McKernan and Karla Ortiz– sued Stable Diffusion, Midjourney and the artist portfolio platform DeviantArt because their works were used to feed its AI algorithms. "These companies have violated our rights by training their AI tools with five billion images from the internet without having the consent of the original artists' ', the Verge reports. "As I learned more about how the deeply exploitative AI media models practice, I realized there was no legal precedent to set this right," Karla Ortiz, tweeted: "Let’s change that."

Karla is a Puerto Rican working in films, games and TV and is a passionate advocate for better artist industries and rights: “I am proud to be one of the plaintiffs named for this class action suit. I am proud to do this with fellow peers, that we’ll give a voice to potentially thousands of affected artists. I'm proud that now we fight for our rights not just in the public sphere but in the courts!”, she adds.

They are not the only ones denouncing the advantage of these AI companies. Getty Images also commenced legal proceedings this January in the High Court of Justice in London against Stability AI, claiming the company had infringed intellectual property rights. “Stability AI unlawfully copied and processed millions of images protected by copyright and the associated metadata owned or represented by Getty Images lacks a license to benefit Stability AI’s commercial interests and to the detriment of the content creators”, as stated in its Images Statement.

"As I learned more about how the deeply exploitative AI media models practice, I realized there was no legal precedent to set this right"

In response to this controversy, another group of artists, Spawning, released the website ‘Have I been trained?’ a couple of months ago, that allows anyone to see if their artwork has been used to train AI algorithms. “It would be impractical to pay humans to manually write descriptions of billions of images for an image data set”, says the AI and Machine Learning Reporter for Ars Technica, Benj Edwards. “They don't seek consent because the practice appears to be legal due to US court decisions on Internet data scraping. But one recurring theme in AI news stories is that deep learning can find new ways to use public data that wasn't previously anticipated—and do it in ways that might violate privacy, social norms, or community ethics even if the method is technically legal”.

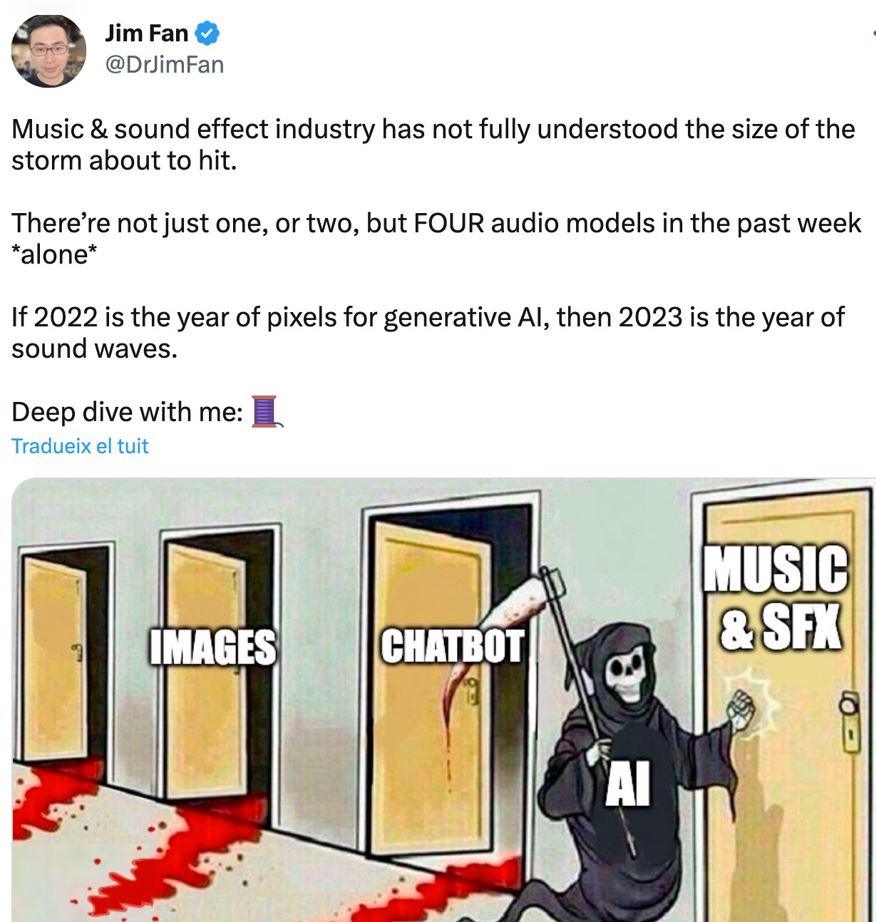

This is the battle so far in the images and text field. We can assume we will be very soon seeing similar reactions in the music sector. In his tweet, AI scientist Jim Fan expresses very clearly the moment we are living in: "The Music & sound effects industry has not fully understood the size of the storm about to hit. There are not just one, or two, but four audio models in the past week alone. If 2022 is the year of pixels for generative AI, then 2023 is the year of sound waves."

Perhaps we should change our expectations about ownership and look for an initiative similar to the Creative Commons licenses (CC) that were created 20 years ago and helped organize permission to use a creative work, suggests Anna Xambó. "I combine works with CC licenses with my own sounds, and you do not know who owns what. Also, there are some pieces that are influenced by the listener. So who owns what? Maybe we should think about coral ownership, accepting a multiplicity of creators and skip the romantic figure of the composer", she concludes.

From artists to audiences

Among the ongoing dilemmas with technology, it's not always obvious where to draw the line between music production and music consumption, as the two parts are interconnected.

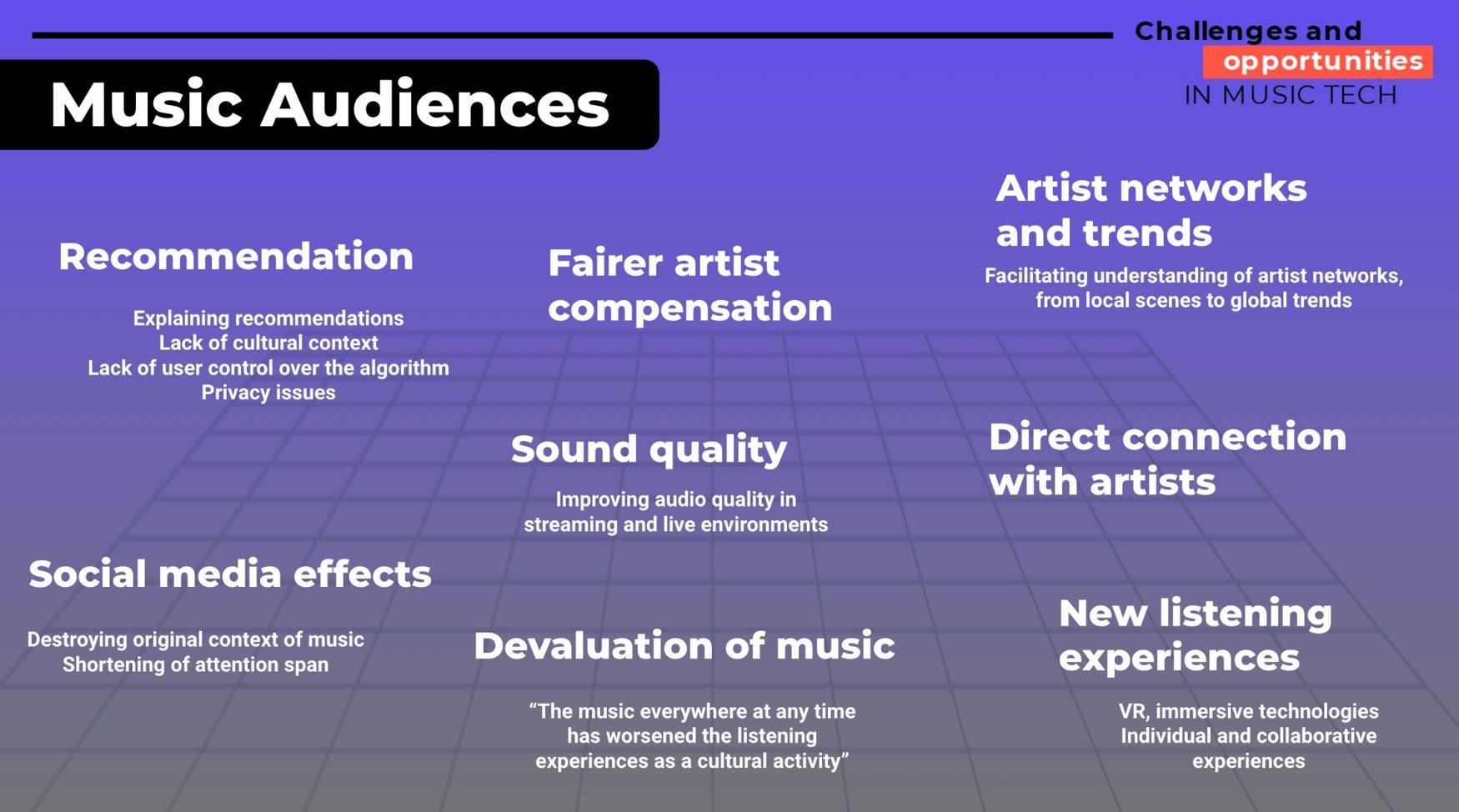

How does music get from the creators to the listeners and what happens in this process when AI intervenes? ‘Algorithmic recommendations’ are described not only as an "outstanding technological achievement" but also as in need of improvement. These systems, which are on platforms such as Spotify or YouTube, among others, are still perceived by professionals as 'black boxes' and give no clue as to why they recommend one song and not another to the listeners. Musicians have to rely on these algorithms to increase their advertising budgets or to reach new target groups. They complain about a lack of control over how these algorithms work.

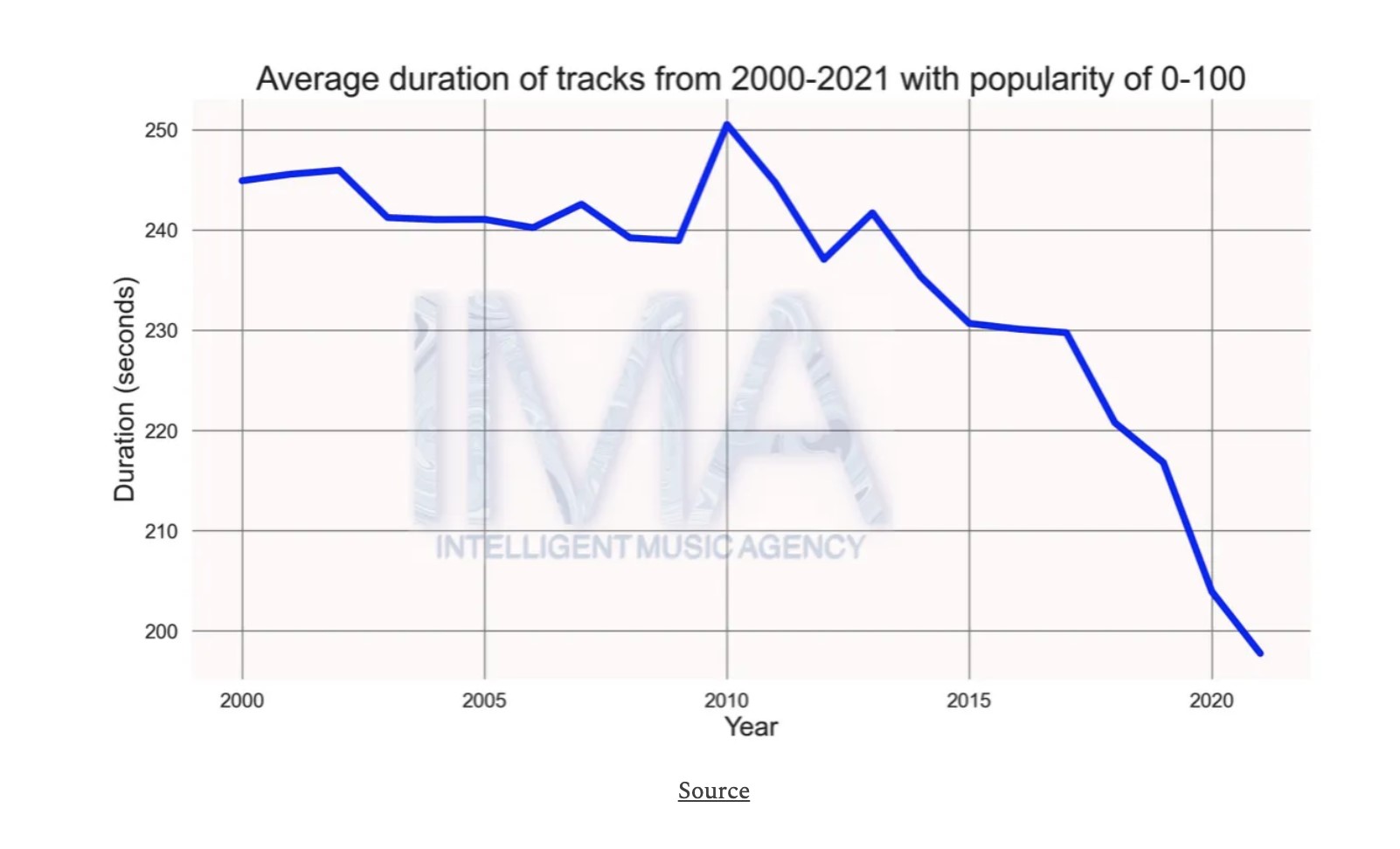

If no one dares go without recommendation algorithms today, the same is true for social media. They are both key for attracting new audiences and retaining existing ones, and a big problem for creators, who are increasingly reliant on large companies to present their work to the public. On the other hand, respondents of the MTG survey identified social media as a potential threat to listening experiences because it destroys the original context of music and encourages a shortened attention span. “Songs have been getting shorter for quite some time, but recently durations have collapsed”, announced the report: “Duration of songs: How did the trend change over time and what does it mean today?” led by the researchers Parth Sinha, Pavel Telica and Nikita Jesaibegjans.

“The downward trend of songs’ durations highlights a clear pattern of the falling attention span of the average music consumer. It also suggests that shorter songs have a higher chance of reaching more listeners and grabbing their attention. It allows the release of more material, which can be spread out over a higher number of shorter songs”, the analysts pronounce. They want to raise awareness about how creativity and personal artistic vision is becoming strongly devalued. How long does a song have to be for us to like it? As an extreme example, the viral song on TikTok has an average duration of 19.5 seconds. “Where is the limit between satisfying the changing user preferences, while also leaving room for innovation?”, the authors of this study demand. “The conclusion here is pretty obvious: despite the innovation and accessibility, there is also an impact on the global music artist mentality in production, creation, and promotion”, they reason.

Other issues raised in the MTG survey concerned the binomial artist-audience, such as the long-held view in the industry that artists need to be better compensated; a concern made even more critical today by the pandemic and the post-pandemic period. From the audiences, there was a call to enable or encourage direct connections with artists and their local audiences, and improve sound quality in both streaming and live environments. Some respondents also suggested enabling "virtual reality experiences", at private and collective events.

Overload and devaluation

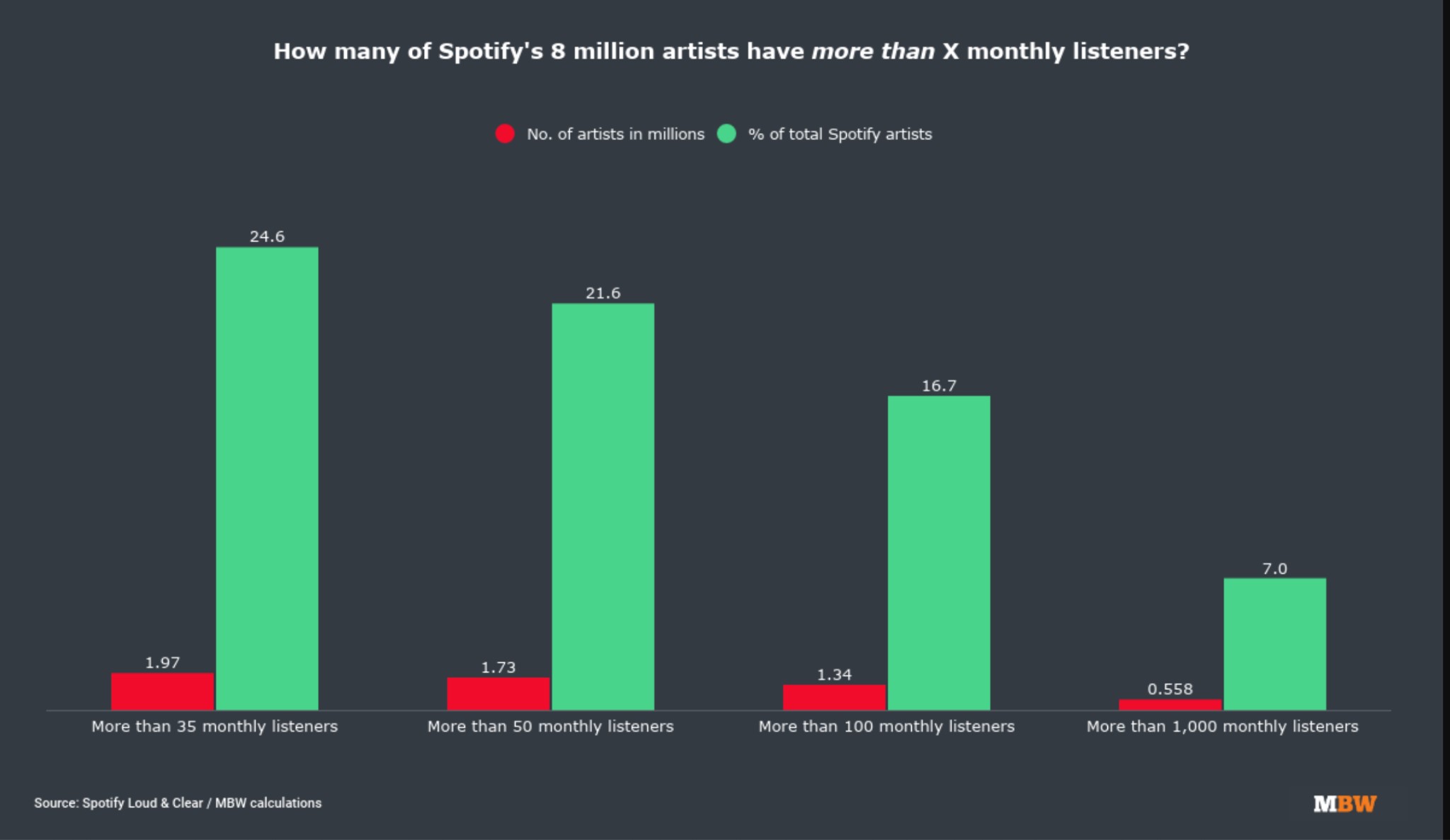

The information overload and devaluation of music on the streaming platforms is another worry: “Music everywhere at any time has worsened the listening experience as a cultural activity”, some survey participants claim. Recently it has been reported that “100,000 tracks are now being uploaded to streaming services each day”, which also makes it increasingly difficult for emerging or even established artists to cut through and be noticed. Whatsmore, nearly 80% of artists on Spotify have fewer than 50 monthly listeners, according to the 2021 annual report of the company.

In the end, what will be the most significant challenges that AI will bring to music audiences? Experts from streaming platforms and AI software developers have the floor now. The senior research director of the PANDORA platform, Fabien Gouyon, urges us to be less pessimistic, to look on the bright side and also consider the opportunities presented by current technology. “One challenge we have is how to find the right interactivity to provide to the user. This could range from listeners just passively pressing "play", to having the capacity to tune the algorithms themselves to their own tastes and according to their own curiosity. What is the right balance for everyone?”.

"100,000 tracks are uploaded to streaming platforms every day, but most artists have less than 50 monthly listeners"

The Head of Innovation at the music technology company BMAT, Gonçal Calvo thinks that the most important challenge today is the overproduction of music. “Digitalization gives us too much abundance and this fact poses issues in terms of copyright management or business models. Is a sustainable economy possible with 100 thousand new tracks every day? I foresee strong tensions in the next year around this issue”. Calvo is of the opinion that companies are incentivizing music created for the platform.”Composers know which stuff will sound better on the playlist and the rewards to come if the song is played for more than 30 seconds. There is a hook and the listener is caught on in”.

Back in 2018, writer and editor based in New York Liz Pelly highlighted this issue in an article for Baffle magazine: "Musical trends produced in the streaming era are inherently connected to attention, whether it's hard-and-fast attention-grabbing hooks, pop drops and chorus loops engineered for the pleasure centers of our brains, or music that strategically requires no attention at all - the background music, the emotional wallpaper, the chill-pop-sad-vibe-playlist fodder," she said. Pelly is currently working on her first book, Mood Machine: The Rise of Spotify and the Costs of the Perfect Playlist, to be published by Astra House in 2024.

As an AI music engineer and consultant to music technology companies, Valerio Velardo believes that the current relationship between artists and audiences may change greatly thanks to emerging technologies. "Today, listeners can become music creators with AI tools. They can share musical experiences through virtual reality and Metaverse; and use platforms to overcome the distance between artists and listeners, as is the case with China's Tencent, where revenues are no longer linked to the stream but are mainly generated through fund-driven approaches." Another, perhaps not so nice, point is that Tencent Music’s streaming services now host over 1,000 songs with AI-generated vocals created by the Chinese company, and all of these tracks are cumulatively amassing millions, if not billions, of plays! Will streaming services take perhaps too much benefit from their advantageous positions, so as to even dethrone the majors?

“You may say I’m a dreamer...”

Or can we imagine a near future in which the music sector does not depend only on streaming platforms? It is true that these companies have huge amounts of data, made up of millions of pieces of data about user behavior, and the more data you have, the better the intelligent systems behind the most popular platforms work. But is it possible to envisage that in five or ten years there may be alternative projects from small companies, music groups or individual professionals who also offer music in other ways as well?

With this in mind, Jordi Pons, a researcher at Dolby Laboratories, explains that a future goal could be to create an easy-to-use workflow which independent artists could use to create new material with AI without having to invest time learning how the tools work. According to the research director of the PANDORA platform, the big changes will not come from the big companies. “You have countless examples so far: BMAT, which began as a start-up and has completely disrupted the music industry over the last 15 years; Moises, which uses techniques of AI audio separation to remove or isolate vocals and instruments, adjust the speed and pitch, and enable metronome counts in any song; and VoctroLabs, founded in 2011 by four music experts has done amazing stuff and was bought by Voicemod, an AI voice augmentation company in December last year”, explains Fabien Gouyon.

Gonçal Calvo of BMAT points out that "no one is free from disruption on this fast path of technology we live in. If copyright disappears, BMAT no longer has any point in existing. Either we reinvent ourselves by understanding what the market needs, or someone else will come along”, says Calvo. “Technology has impacted on the music sector. Just remember how your parents listened to music when you were a kid, then consider how your children will do this".

“Bridging the gap”

Another dream for the coming years is to improve the connections between artists and listeners. How can this be achieved? What strategies already exist in the music industry that could see the light of day in the near future? "The most important thing is the way they can interact. The big Chinese company Tencent is moving from a stream-based revenue model to a fund-based revenue model," explains Valerio Velardo. "This allows artists to come together with listeners at certain moments in order to get paid. For example, when an artist meets with fans, or when the audience sings karaoke, etc. Through this model, which is based on the idea of tokenizing the relationship between artists and listeners, they can earn a fair living. We have not yet explored that in the West, but the disruption of the business is now coming from the Chinese market. Because the real value of music is in these unique experiences".

Networks that link artists and fans is not an entirely new concept. A couple of decades ago, Last.fm, a music website founded in the United Kingdom in 2002, used a music recommender system to build a detailed profile of each user's musical taste by recording details of the tracks the user listens to, either from Internet radio stations, or the user's computer or many portable music devices. This information was transferred ("scrobbled") to Last.fm's database either via the music player (including, among others, Spotify, Deezer, Tidal, MusicBee, SoundCloud, and Anghami) or via a plug-in installed into the user's music player. The data was displayed on the user's profile page and compiled to create reference pages for individual artists. The site formerly offered a radio streaming service, which was discontinued in 2014.

“Business disruption is now coming from the Chinese market. The real value of music lies in these unique experiences.”

Can today’s technology improve on what Last.fm could provide at the time? “With the technology that's been developed in the last 20 or 25 years, we have opportunities that we never had before”, Valero thinks. “And I am not just talking about AI music. There are thousands of artists who have discovered Bandcamp, this online record store music community that gives you chances that I never had as a kid”. And as the research director of PANDORA, Fabien Gouyon states, "people will still physically go to a concert, and they will recommend music to their friends without going to a computer. Recommenders will not replace everything."

Wish list for the future

If we made a list with must-haves for the coming years in terms of music creativity and music listening, what would be on it? And what would we want to avoid? “I would like to see new genres of music appearing, new sounds, new dances, different instruments, different ways of performing”, says curator Antonia Folguera. “I would not like to see streaming platforms releasing cheap AI generated music”, adds the artist Rob Clouth.

“I would like to see more customized systems, unique experiences for each human and non-human listener, music that is not influenced by humans. As for potential fears... the production of boring music, all produced using the same tools, the homogenization of Western music. And systems becoming ‘black boxes’. When they become more and more complex, there is no transparency, and it's important to see what is behind the scenes”, reflects the researcher Anna Xambó.

“We have in our hands nowadays tools to democratize access, to give a voice to everyone and to make it possible to earn money in ways that are impossible today. There is a place for everyone, we need to invest in the idea that great things will happen. We have to have courage and understand the necessary tools to move forward”, concludes the lawyer Marcelo Estrella.

A world of tremendous possibilities is opening up, and people will know how to take advantage of them. An era of individualized and customized use and enjoyment of music is on the horizon. Or just imagine the idea of therapeutic music based on bio/neurofeedback. Or music that tracks and reacts to our emotions.

What is to be human?

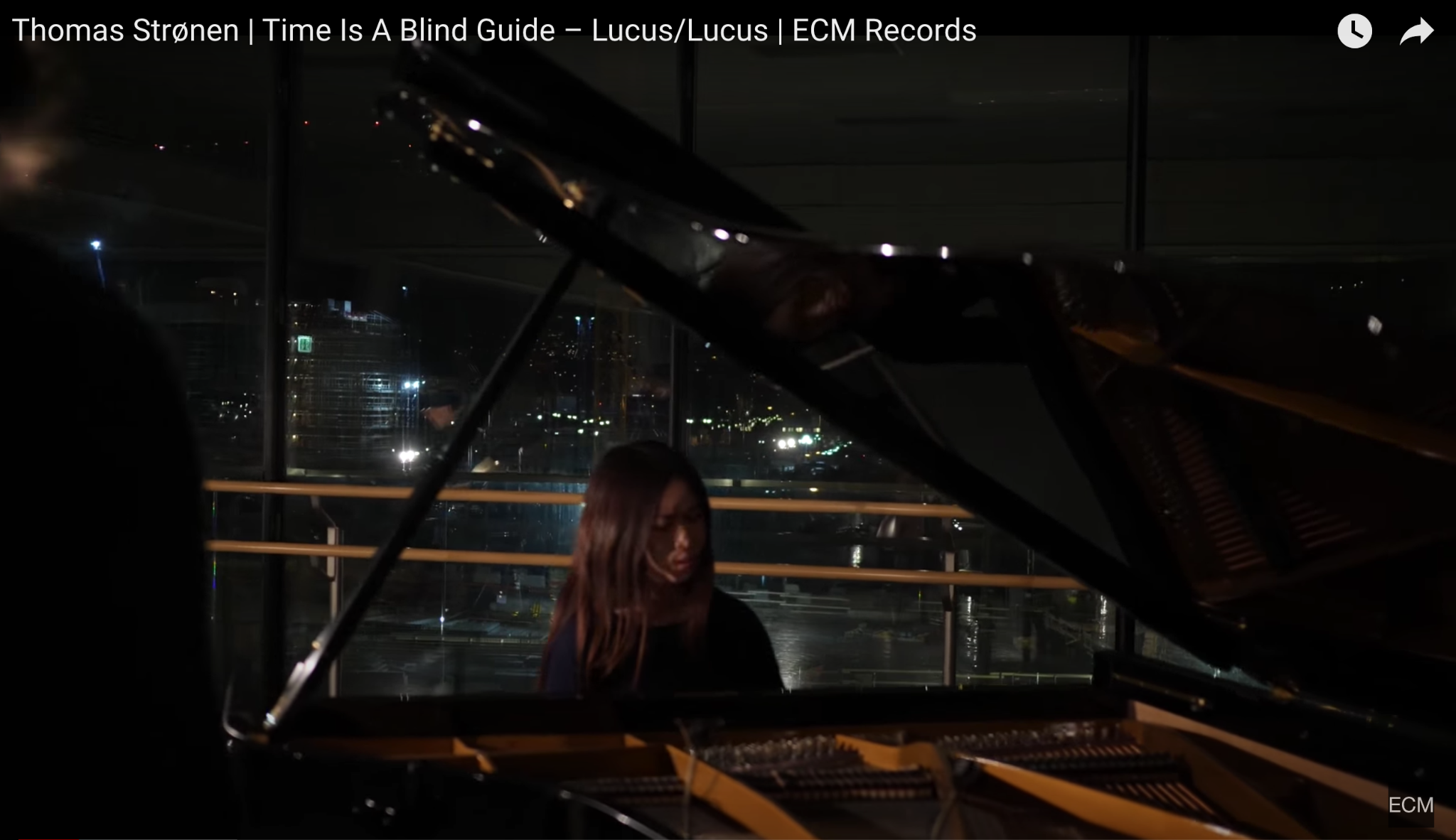

Late February 2023. The Auditori of Barcelona programmed an intimate concert of jazz music that could be classified as chamber music. On stage is one of Norwegian drummer Thomas Strønen's latest projects: 'Time is a blind guide'. His band - violinist Håkon Aase, Leo Svensson Sander on cello and Ole Morten Vågan on double bass - are accompanied by the exquisite Japanese pianist Ayumi Tanaka. It is an hour of pure improvisation, where the music flows in perfect connection between the musicians and the audience. The compositions are only a guide. The visual language of looking into each other's eyes is enough for the players to know how to evolve and when to stop playing. Before the concert ends, the leader of the group asks a Turkish musician to come on stage, and he plays a delicate flute with intimate reminiscences. The mix of cultures, sensibilities and artistic prowess makes this concert particularly unique: "I am lucky to be surrounded by incredible human beings and fantastic artists," says Strønen at the end, and the audience applauds in appreciation of an exceptional encounter.

Take a moment to consider what music means to humankind. Aside from enjoyment and connection with others –and as a source of revenue for the industry and professional musicians–, it is of huge cultural significance in terms of history and traditions, spirituality and religious practices. “Music is universal, transmitted through generations, usually performed in the presence of others, and of extreme antiquity”, say the authors of the scientific article: «Cross-cultural perspectives on music and musicality». Will AI and the emergent technologies also have this power to make us feel that we belong to, or are separate from, a social group?

Music everywhere is believed to affect our emotions, to involve some kind of arousal, “ranging all the way from mild pleasure or displeasure to profoundly transformed states of consciousness”, asserts the scientific article. Will artificial intelligence be able to stir up these feelings, stimulate the senses and make us feel awe and connection in the same way? If so, does this dilute or even remove something that makes us human? Is this question still relevant in a globalized world where technology is already so embedded?

We are still floating along in the clouds, with few clues as to where we will end up. There are many questions without answers but what we do know is that there may be turbulence ahead.

Methodology: How did we get here?

This article summarizes the main conclusions of the Challenges and Opportunities in Music Tech project led by MTG. It is just a start, a way to organize the current discussion about how AI and new technologies will change the music sector in the coming years. The aim of the project was to listen, gather the opinions of key stakeholders and share them.

The team spent four months interviewing industry executives, music creators, listeners, music students, archivists and developers. "We wanted to contribute to the industry by organizing these discussions," says the director of MTG, Xavier Serra.

The team started with a form, a questionnaire, and tried to divide the topics of interest into four areas: 'Music creation', 'Music listening and audiences', 'Music education' and 'Music archives'. The first stage was to gather responses from more than 80 international and local experts in the music sector.

The second phase was to select ten experts to explore these topics in-depth with music creators, researchers, music developers, teachers, music curators, and artists in a series of 10 interviews, each lasting over an hour.

The last step was to put on an open, face-to-face event with the audience. In order to design what this meeting should look like, the team had to collate the work that had already been done (conclusions from the surveys and the interviews) and weigh up how the main issues could be summarized for discussion. It was clear that the main topic would be artificial intelligence, but the MTG also wanted to bring in opinions that are sometimes not represented in the general media. "At the same time, it was our intention to present as many different voices as possible because this debate cannot only be held within one field - whether that be academia, industry or politics. It has implications for everyone. That's why everyone needs to be involved in the discussion," says Serra.

Having access to both the knowledge and the latest technological developments, the MTG had to ensure that everyone heard each other's views. So, in two discussion panels: “Music Creation” and “Music Listening”, eight music sector representatives shared their views on the benefits, opportunities, risks, fears and ethical issues, in a debate lasting four hours.

"The listeners -who are not usually heard or considered, but who are crucial because they are the ones who buy and consume music and go to concerts – must also be represented in our project. We also wanted to let the people who are not part of the companies have their say." Xavier Serra adds.

The debate across all spheres and with all stakeholders, has only just begun. The next step for the MTG is to learn from the results of this debate to define its research priorities. There are huge opportunities for developing new and better IA technologies that accompany all music stakeholders. However, it is clear from the opinions raised that these technologies should prioritize ethical concerns and be transparent in front of society.

Special thanks to the professionals who contributed to the project by participating in in-depth interviews and as panelists in the open debate:

- Malcolm Bain: Lawyer. Across Legal

- Gonçal Calvo: Head of Innovation. BMAT

- Oscar Celma: Director of Engineering. Spotify

- Rob Clouth: Music Creator

- Marcelo Estrella: Lawyer. Across Legal

- Antonia Folguera: Curator. Sónar festival

- Cristina Fuertes: Music Teacher. Institut Obert de Catalunya (IOC)

- Emilia Gómez: Senior Researcher. Joint Research Center (European Commission)

- Fabien Gouyon: Director of Research. Pandora

- Rujing Huang: Ethnomusicologist and Musician. University of Hong Kong

- Luca Andrea Ludovico: Researcher. Laboratory of Music Informatics (University of Milan)

- Jordi Pons: Researcher. Dolby

- Jordi Puy: CEO. Unison rights.

- Raul Refree: Music Creator and Producer

- Robert Rich: Music Creator and Producer

- Valerio Velardo: Consultant on AI and music

- Anna Xambó: Researcher and Music Creator. Institute of Sonic Creativity (DeMontfort University)

And also thanks to everyone who participated in the opinion-gathering survey

The Music Technology Group (MTG) of the Universitat Pompeu Fabra in Barcelona has extensive experience in carrying out research projects with an impact on society. Created in 1994, the research group has more than 30 members who work on different topics related to the technologies applied to music creation, understanding, consumption, education and wellbeing. Some of the most popular products arising from the research group's projects are: Reactable (interactive digital instrument), Vocaloid (singing voice synthesizer) or Freesound (sound exchange platform).

Specifically, the group has an extensive experience in research and development of recommendation systems, and has studied the impact of music technology in the cultural and gender diversity, publishing scientific articles on these topics. The fact that the MTG is a research group in the intersection of the music and the technology sectors, facilitates that the group can foster this balanced dialogue between the different agents, and also, thanks to its almost 30 years of active work, has a great influence in the scientific community and the capacity to achieve a relevant impact in the future development of AI.

The project “Challenges and Opportunities in music tech” has been conducted by the researchers Xavier Serra, Sergi Jordà, Dmitry Bogdanov, Frederic Font Corbera, Marius Miron, Perfecto Herrera, Sònia Espí and Lonce Wyse.

*Karma Peiró is an external collaborator with the MTG. She has specialized in Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) since 1995 and is co-author of the Report: «Artificial Intelligence. Automated Decisions in Catalonia», by the Catalan Authority of Data Protection. She is a lecturer in seminars and debates related to data journalism, the ethics of artificial intelligence, transparency of information, open data and digital communication.

This project is supported by MusicAIRE initiative (funded by the European Union under Music Moves Europe program), and Ajuntament de Barcelona.