His works

“Cada cop més, el cinema de ficció té més elements de documental i, al mateix temps, el que abans s’entenia com documental està incorporant elements de ficció d’un mode o altre. No és de ficció perquè hi intervinguin actors. El documental és una mirada de la realitat però que es manipula constantment, no és un reportatge sinó una elaboració a partir de fets reals. Les diferències no són tan clares”

(Joaquim Jordà entrevistat per María Ángeles Cabré i Dolors Udina en 2003, Vasos Comunicantes Nº 26)

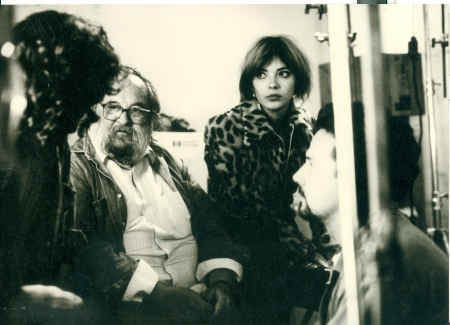

Among the different reflections there are on Jordà’s cinematographical works, there’s a quality that usually surfaces, almost omnipresent: the director’s lack of style. This concordance, which emerges from various texts, is not a synonym for a certain artistic promiscuity, but for a “singular process that challenges genre” (Guerra, 2014), for an expressive and creative freedom that gives room to hybridization: “more than a determined style, what defines his cinema is the heterogeneity that results from his will to utilize everything in his favour in order to conduct us towards the reflection he seeks'', Liberia Vayá points out (2012).

In that lack of style, such hybridization is manifested in the bond between documentary and fiction, “which makes us often wonder when the director is limiting himself to filming a scene that is occurring more or less spontaneously, and when is he himself who is provoking and organizing it” (Liberia Vayá, 2012). We can also identify the presence of a pairing of different formats and materials through the combination of “fictional scenes with professional actors [and] classic documentary sequences, fictional reconstructions, filmed theatre, interviews or archive images. The filmmaker films with great liberty, letting himself go with the hazards of shooting and walking through unplanned roads” (Liberia Vayá, 2012).

For Benavente and Salvadó, nonetheless, that “showcasing of reality from an unusual perspective” can be identified as a characteristic that is usual of all of Jordà’s films, “the revelation of hidden aspects –despite being on plain view-, the situating of the audience always on the other side of the mirror in order to discover the reality of the reflected world, which it already knows, but not in that way” (2009). For both of them, in this specular relationship, “this venturing into the field of the Other is the ethical principle that determines the political power of his cinema: the fact that he stands side by side with positions that escape the reductions of order or the perceptions of normality” (2009).

As “conversationalist-filmmaker”, the alexia and agnosia he begun to experience after a stroke in 1997 highlight even more what Salvadó and Benavente consider one of his main dialectics, that between the word and the image: “in a cinema like his, in which the word, especially the oral story, constructs the film and determines the image, it is essential to arouse, model, question the discourse of the person speaking in order to reveal the narration sought” (2009).

This way, Jordà’s cinema, in the words of his collaborator Laia Manresa, “does not delight, nor is it self indulgent, but rather shakes, sweeps, pisses off” (2006). It isn’t worried by aesthetic formalisms, but with limits, discomforts, with “staring into the eyes of things that are not pleasant, like death, suicide, the impossible fight against capitalism, insanity or pedophilia” (Manresa, 2006). It is because of that, Manresa adds, that “his cinema is ruthless and alive, it breathes freedom. Or, better yet, it’s a cinema with an impetuous and terrible desire for freedom” (Manresa, 2006).

“Són com dues parts del cos diferents les que es posen en joc [a la traducció i al cinema]. Traduir és una activitat molt sedentària que afalaga la meva part sedentària. M’encanta no moure’m, però hi ha moments en els quals m’encanta moure’m, i la part de director de cinema m’obliga a moure’m (...). En certa mesura, he tingut la sort de poder fer coincidir els meus estats d’ànim amb activitats que són absolutament oposades, tot i que tenen alguna cosa en comú”

(Joaquim Jordà entrevistat per María Ángeles Cabré i Dolors Udina el 2003, Vasos Comunicantes Nº 26)