Altruistic behaviour is conditioned by the social environment, not just by the nature of the person

Altruistic behaviour is conditioned by the social environment, not just by the nature of the person

Such is the proposal of a study led by Salvador Soto Faraco, ICREA researcher and member of the Center for Brain and Cognition, together with Juana Castro Santa, alumna of the master’s degree in Brain and Cognition, and Filippos Exadaktylos, a researcher linked to the UAB, in a paper recently published in the journal Scientific Reports.

People who care for others and whose behaviour is conditioned by doing them good are said to behave altruistically. Often, altruism has been understood as being the opposite of egoism. A recent study published in Scientific Reports looks into whether people are altruistic or not by nature and if cooperation is the cognitively rapid and preferred option by human beings.

In recent years, the question as to whether cooperation among humans is intuitive or not has generated great interest among researchers. To address this question, some studies have focused on measuring response time in cooperation dilemmas, assuming that faster decision times are, of course, those that coincide with the person’s natural tendency. ”Here we defend that the immediate social environment, and not just the nature of the person, shapes willingness to cooperate and, therefore, response latencies”, says Salvador Soto Faraco, co-author of the study, ICREA researcher with the Department of Information and Communication Technologies (DTIC) and a member of UPF’s Center for Brain and Cognition (CBC), together with Juana Castro Santa, alumna of the master’s degree in Brain and Cognition at the CBC, and Filippos Exadaktylos, a researcher linked to the UAB.

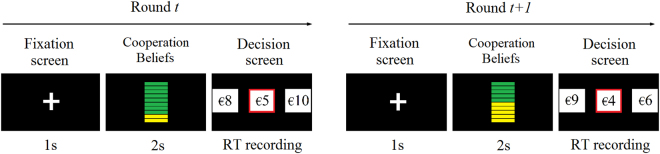

A few years ago it was argued that altruistic responses are faster than purely egoistic ones, reflecting humans’ cooperative nature. The aim of the study published in Scientific Reports was to find out whether this relationship between decision time and altruism depended on the social context. “Hence, we posed to the participants in the study a social cooperation dilemma approached as a game in which they were not quite sure what would be their game partner’s decision, but they were informed of their intentions, insofar as the likelihood that they would betray them or collaborate with them. This “social” ratio was gradually varied”, explain the authors of the study.

Through this game based on a dilemma of cooperation, “we manipulate a person’s beliefs about the other player’s intention to cooperate. When the partner’s intention to cooperate is perceived as high, response times show that the options of cooperation speed up and the options of disloyalty slow down”, says Soto-Faraco. The dilemma incites the participants to choose between two options of an economic nature, one which involves betraying the partner (who they do not know) to win as much money as possible, and the other option involves collaborating with them and both of them end up winning the same. If the gains through betrayal or collaboration are varied, it is observed that if betrayal leads to a much higher profit than cooperation, then betrayal results in being far more tempting. In this scenario, betraying or helping will depend on the profits earned.

“What we found is that, depending on the social context, the fastest, most natural responses could be both altruistic or egoistic. That is to say, beyond the nature of the person, the social context determined the likelihood that the participant would collaborate or take advantage of the others”, says Castro Santa, first author of the study.

From this experience it becomes clear that beyond asking ourselves if the human species is altruistic or selfish by nature, we might think that we have a switch that predisposes us in one direction or another according to what we think about the intentions of the people in our social environment.

Soto Faraco illustrates this with the following example: “if you see someone drop something, you might want to help and, automatically, you kneel down and pick up the fallen object; but if you perceive that the person has thrown it to the ground on purpose, rarely will you have the intention of helping”.

These results reveal new approaches to the role of conflict in the decision-making process explained through response latencies, as well as on the hypothesis that cooperation is the intuitive option for human beings. This research may help to properly interpret and reconcile apparently contradictory results obtained in previous studies, looking now at the role of context in social dilemmas.

Article:

Juana Castro Santa, Filippos Exadaktylos, Salvador Soto Faraco (2018), “Beliefs about others’ intentions determine whether cooperation is the faster choice”, 14 of may, Scientific Reports 8, 7509.