Paternity leave does not solve the gender division in the tasks of parenting

A study by Libertad González and Lídia Farré, lecturers at UPF and UB respectively, analyses the effect of the introduction of paternity benefit in Spain in 2007 on the employment situation and birth rate within the family.

What is the social impact of increasingly generous maternity and paternity benefits? Do these policies promote a more balanced contribution between the sexes in caring for children? Do they serve to reduce discrimination against women in the labour market? What influence do they have on the employment status of fathers and mothers and on the birth rate?

“The Effects of Paternity Leave on Fertility and Labor Market Outcomes“, a paper by Libertad González, linked to the Department of Economics and Business at UPF and to the Barcelona GSE, and Lídia Farré, professor at the University of Barcelona and researcher at the Institute for Economic Analysis (IAE-CSIC), seeks to help provide answers to all these questions.

The study, published in the series Barcelona GSE Working Papers (No. 978), analyses the effects of the law that the Spanish State Government passed in March 2007, that offers two weeks of exclusive leave to the father, in addition to the sixteen weeks of leave granted to the mother, and proposes some measures for improvement in order to achieve effective gender equality.

The results of the study (which do not yet include the reform of January 2017, which introduced four weeks of leave for fathers) suggest very limited effects of paternity leave in altering social norms and domestic behaviour in the long term, beyond the specific period of paternity leave, as well as in reducing gender inequality in the labour market.

Effects on the labour market and the birth rate

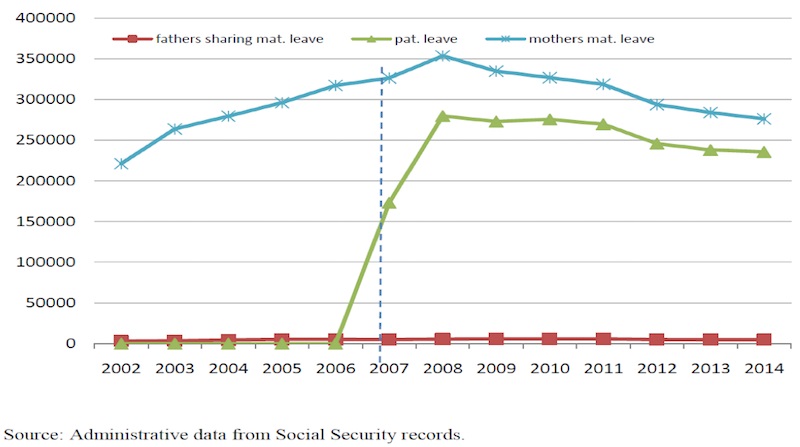

According to the study, the introduction of the two weeks of paternity leave (of the type “use it or lose it”) increases the rate of enjoyment by fathers of this type of leave by some 400% compared with the average prior to the legislative reform. So, one year after its implementation (in 2008), 54% of all new fathers enjoyed such leave, whereas before the reform almost no one took advantage of it.

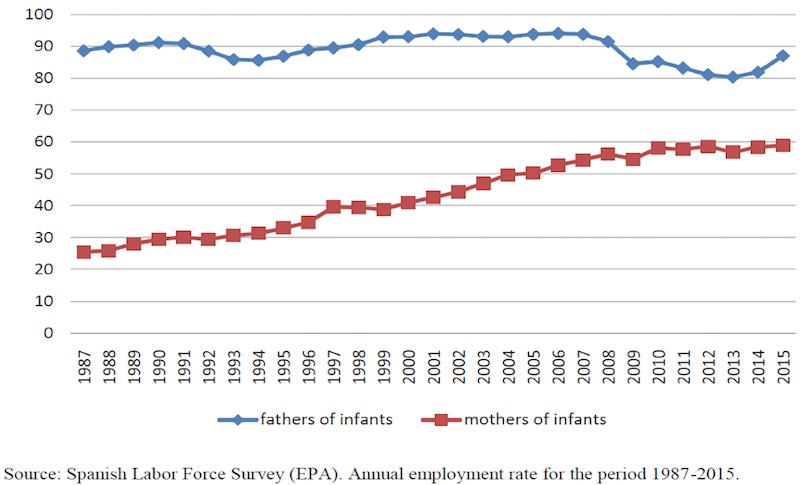

This measure generated an 11% increase in the likelihood of the employment of mothers shortly after the birth of the child, in addition to reducing the incentives for taking extended unpaid leave, while for fathers there are no notable employment changes. However, these effects in the short term do not bring about long-term changes in the employment of mothers or in the participation of fathers in the parenting of their children.

In addition, the new policy delayed fertilization and reduced births by 15%, a decrease in birth rate that mainly affected people without university education and women over 35 years of age.

According to the authors, the drop in birth rate is driven by the decision among older couples to postpone parenting, and may be caused by the potential increase in cost in raising children as a result of the participation by fathers in paternity leave and the early return to work by mothers. This decrease contrasts with the results of previous studies conducted in other countries that found that the introduction of this type of leave did not affect the birth rate.

The study also detects differences according to the people’s qualifications and training: more qualified parents are less likely to take the leave, whereas with regard to mothers, the probability of having work after the reform of the law only increases for less qualified women.

The work methodology is based on a discontinuity regression design to quantify the effects of the introduction of paternity leave, and uses various data sources. For the empirical analysis, most of the results are obtained from the Labour Force Survey, which contains information about the employment market and family birth rates. Farré and González complement their analysis with data from the Social Security (Continuous Work History Sample), with information on employment results and status, as well as records of birth certificates.

There is a need for an optimal combination of family policies for real gender equality

The authors emphasize that these results suggest that there may be a limited influence of public intervention to alter the social or cultural norms that govern the persistent gender division of domestic tasks, and they note that further research is required to identify the right combination of family policies in order to achieve full gender equality in the home and in the labour market.

Libertad González and Lídia Farré suggest that a more intensive reform, such as matching the duration of maternity and paternity leave, could have a more notable effect on the division of parenting tasks. They also warn of the unwanted effects on birth rate, which are worrying in countries with low birth rates, like Spain, and propose the possibility of introducing other policies, such as subsidized child care.

Reference work: González, L. and Farré, L.; ”The Effects of Paternity Leave on Fertility and Labor Market Outcomes”, Barcelona GSE Working Paper (Nº. 978)