What did people eat in Switzerland in the Bronze Age?

What did people eat in Switzerland in the Bronze Age?

Scientists from Geneva and Pompeu Fabra universities have analysed the skeletons of several Bronze Age communities that lived in Western Switzerland in order to reconstruct the evolution of their diet. The article, published in PLOS ONE and led by Alessandra Varalli, currently linked to the UPF Department of Humanities, who participated in the research when he was doing his postdoctoral fellowship at the University of Geneva, shows that there has been a radical change in eating habits since the introduction of new cereals.

The Bronze Age (2200 to 800 BC) marked a decisive step in the technological and economic development of ancient societies. People living at the time faced a series of challenges: changes in the climate, the opening up of trade and a degree of population growth. How did they respond to changes in their diet, especially in Western Switzerland? A team from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), Switzerland, and Pompeu Fabra University (UPF) in Spain has for the first time carried out isotopic analyses on human and animal skeletons together with plant remains.

"We could study the stable isotopes of collagen of the bones and teeth of human and animal skeletons and define their living conditions".

The scientists discovered that manure use as a fertilizer had become widespread to be able improve crop harvests in response to demographic growth (intensification of production), and found that there had been a radical change in dietary habits following the introduction of new cereals, such as millet. In fact, the spread of millet reflected the need to embrace new crops following the drought that ravaged Europe during this period. Finally, the team also showed that the resources consumed were mainly terrestrial. The research results, which has had the collaboration of the universities of Neuchâtel (UNINE) in Switzerland and Aix-Marseille (Lampea, France), have recently been published in the journal PLOS ONE.

The Bronze Age marks the beginning of today's societies

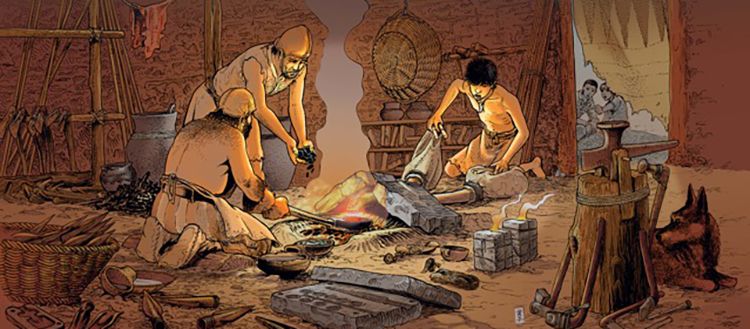

Today, archaeological resources for studying the Bronze Age are limited. “This is partly down to changes in funeral rituals,” begins Mireille David-Elbiali, an archaeologist in the Laboratory of Prehistoric Archaeology and Anthropology in the F.-A. Forel Department in UNIGE’s Faculty of Sciences. “People gradually abandoned the inhumation practice in favour of cremation, thereby drastically reducing the bone material needed for our research. And yet the Bronze Age signals the beginning of today’s societies with the emergence of metallurgy.” As the name suggests, societies began working with bronze, an alloy consisting of copper and tin. “And this development in metallurgy called for more intensive trade so they could obtain the essential raw materials. This increased the circulation of traditional crafts, prestigious goods, religious concepts and, of course, people between Europe and China,” continues the archaeologist.

Diet imprinted in bones

The Neolithic Age marked the inception of animal husbandry and the cultivation of wheat and barley. But what about the diet in the next Bronze Age? Archaeobotany and archaeozoology have been routinely used to reconstruct the diet, environment, agricultural practices and animal husbandry in the Bronze Age, but these methods only provide general information. “For the first time, we decided to answer this question precisely by analysing human and animal skeletons directly. This meant we could study the stable isotopes from the collagen of the bones and teeth that constitute them and define their living conditions”, continues Alessandra Varalli, a researcher in UPF’s Department of Humanities, member of the Culture And Socio-Ecological Dynamics Research Group (CaSEs) and the first author of the study, which he carried out during his postdoctoral fellowship at UNIGE.

“In fact, we are what we eat,” points out Marie Besse, a professor in the Laboratory of Prehistoric Archaeology and Anthropology in the F.-A. Forel Department at UNIGE. Biochemical analyses of bones and teeth will tell us what types of resources have been consumed.” 41 human skeletons, 22 animal skeletons and 30 plant samples from sites in Western Switzerland and Haute-Savoie (France) were studied, ranging from the beginning to the end of the Bronze Age.

No differences between men, women and children

The study’s first outcome showed that there was no difference between the diets of men and women, and that there were no drastic changes in diet between childhood and the adult phase of these individuals. “So, there was no specific strategy for feeding children, just as men didn’t eat more meat or dairy product than women. What’s more, when it comes to the origin of the proteins consumed, it was found that although Western Switzerland is home to a lake and rivers, the diet was mainly based on terrestrial animals and plants to the exclusion of fish or other freshwater resources,” adds Alessandra Varalli. But the main interest of the study lies in plants, which reveal societal upheavals.

Agriculture adapted to climate change

“During the early Bronze Age (2200 to 1500 BC), agriculture was mainly based on barley and wheat, two cereals of Near Eastern origin that were grown from the Neolithic Age in Europe", explains Alessandra Varalli. “But from the late Late Bronze Age (1300 to 800 BC), we note that millet was introduced, a plant from Asia that grows in a more arid environmen".In addition, nitrogen isotopes revealed that manuring was used more intensively. “The analysis of several plant species from different phases of the Bronze Age suggests that there was an increase in the practice in soil fertilisation over time, that boost the production of agricultural crops.”

These two discoveries combined seem to confirm the general aridity that prevailed in Europe during this period, which meant agricultural practices had to be adapted; and that there was heightened trade between different cultures, such as Northern Italy or the Danube region, leading to the introduction of millet into Western Switzerland.

These two discoveries combined seem to confirm the general aridity that prevailed in Europe during this period, which meant agricultural practices had to be adapted.

These new cereals might have played an important role in the security of supply, and perhaps contributed to the population increase observed in the Late Bronze Age. In fact, millets grows more quickly and are more resistant to drought and for this reason they are more resilient, at a time when the climate was relatively warm and dry. Finally, the use of fertiliser went hand-in-hand with a general improvement in techniques, both agricultural and artisanal. “This first study on changes in diet in Western Switzerland during the Bronze Age corroborates what we know about the period. But it also demonstrates the richness of the widespread intercultural exchanges,” states Professor Besse with enthusiasm. We still have much to learn about this millennium, in spite of the scientific problems related to the paucity of available material. “This is one of the reasons that led me to excavate the Eremita cave with UNIGE students. Located in the Piedmont region of Italy, it is dated to the Middle Bronze Age around 1600 BC,” concludes Professor Besse.

Reference article: Varalli, A., Desideri, J., David-Elbiali, M., Goude, G., Honegger, M., Besse, M. "Bronze Age innovations and impact on human diet: A multi-isotopic and multi-proxy study of western Switzerland "(2021, January), PLOS ONE.