When the orchestra stops playing: researching the key elements concerning cancer development

When the orchestra stops playing: researching the key elements concerning cancer development

Cancer is nothing more than “the excessive growth of cells that have lost their identity and function” and, to a great extent, it is regulated by a single protein.

Cancer is the main cause of death worldwide. Nearly one in six deaths are caused by the disease. “If we fill a room with people and ask them if they know anyone who has had cancer, most of them will raise their hand”, explains Júlia Urgel, a doctoral student at the Cancer Biology Laboratory. And “seeing such a deadly disease from so close up is a stimulus for many researchers”, who like Julia, are trying to find solutions to it.

Cancer is nothing more than “the excessive growth of cells that have lost their identity and function”, says Etna Abad, a doctoral student in the same laboratory. A situation of cellular chaos that is often due to the cell losing essential proteins for suppressing the emergence of tumours, such as p53.

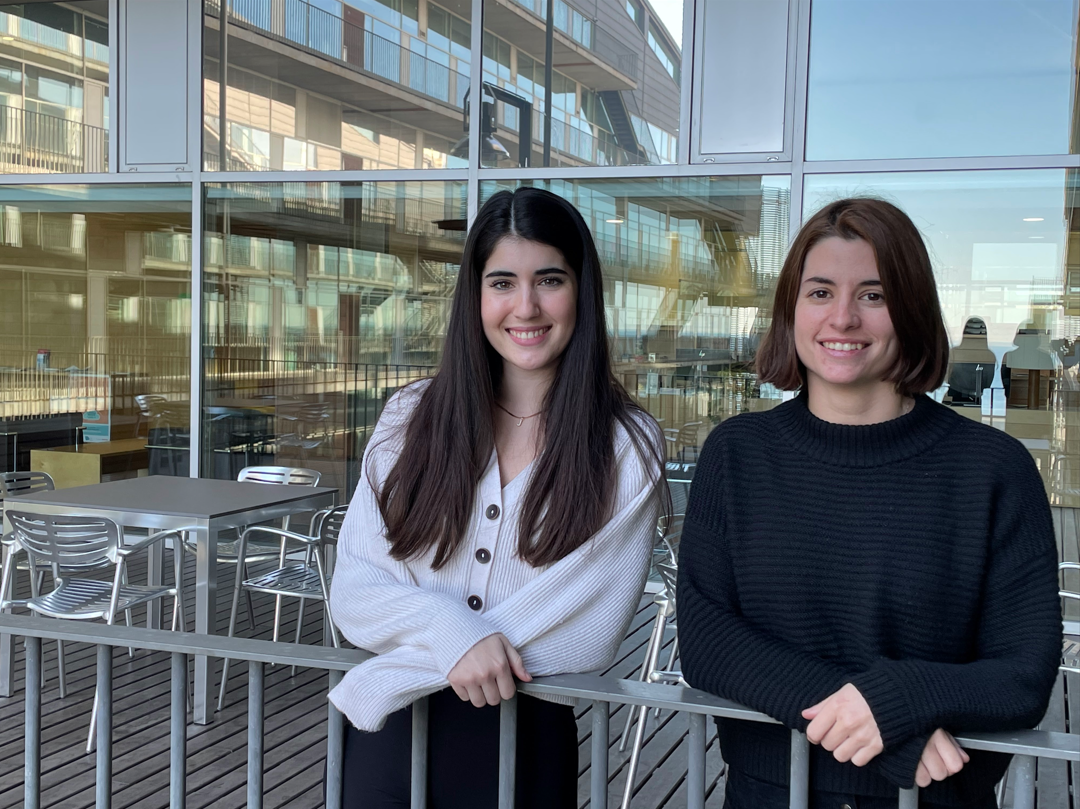

On the occasion of World Cancer Day, we are talking to Júlia Urgel and Etna Abad so that they can explain how, at the Cancer Biology Laboratory of the Department of Medicine and Life Sciences (MELIS), they are conducting research in order better to understand this disease.

In your group all the research hinges around p53. What makes this gene so special?

E. A.: p53 is like the conductor of an orchestra. It helps the cell to manage and regulate the cell cycle, nutrient use, division, death, etc. All of the processes that would make up its symphony. If something happens to this conductor and it does not work properly, it begins to give erroneous indications and all these mechanisms will begin to fail.

J. U.: In the cell, p53 orchestrates many other proteins that help us not to develop cancer. This is so much so that in 50% of cancer cases, p53 is mutated. And right now, we don’t have effective therapies to directly treat cancers with mutated p53. So, we are trying to understand what happens when p53 and the instruments of its orchestra fail and to find solutions to it.

What do you do at the Cancer Biology Laboratory?

E. A.: We all study the role of p53 in one way or another. In my case, I have focused on a protein regulated by p53 that is a tumour suppressor in lymphomas. And I am trying to see if it is also important in other types of cancer, such as lung cancer.

J. U.: I, however, have focused on studying cell metabolism. That is to say, how the cell obtains energy and how it takes the pieces to build everything it needs to function properly. Cancer cells have a slightly different metabolism and I’m trying to see what are the most important elements, apart from p53, to regulate these changes, and trying to find therapeutic targets.

Therapeutic targets sounds huge!

J. U.: Ultimately, I want to find the genes of the metabolism that are essential for a cancer cell with p53 mutation to survive. If we identify these genes and see that, in addition, they are not essential genes for the survival of healthy cells, we will have a target. A clue as to where we can begin to design a selective treatment against this type of cancer.

How do you look for these targets?

J. U.: We use the CRISPR technique, which are nothing more than genetic scissors that, given a template, recognize a region of DNA and cut it so that it stops working. Thus, everything that is regulated by the gene we have cut will stop working. If after the cut the cell does not survive, we know that the cut gene is essential for its survival. Because without it, it's vulnerable.

You are in the Laboratory, in a research centre; but you are already thinking about a possible clinical application!

E. A.: We always have therapy in mind! But it is true that we must first understand how cancer cells work and what differentiates them from healthy ones. Understanding which signalling pathways are active, how the different proteins “speak”, etc. to eventually design a specific and concrete therapy. And yes, we are just starting out, but we are looking at how cells respond to different treatments that are already used in clinical practice.

J. U.: In the end, we do translational research, and we want this basic research to end up being a real and effective treatment for patients.

Do you work with other groups to do this?

E.A: We work with other groups that have more experience than us in areas such as immunology or metabolism and we try to create synergies to go further.

J. U.: So much so that we even have shared projects, such as my doctorate that I am doing straddling two laboratories: the Cancer Biology laboratory, directed by Ana Janic at MELIS-UPF and the Genome Biology Laboratory, directed by Sara Sdelci, at the Center for Genomic Regulation, here at the Biomedical Research Park of Barcelona.