“In a science career you often need luck, but if you put in a lot of time and effort, you are sure to find it”

“In a science career you often need luck, but if you put in a lot of time and effort, you are sure to find it”

“In a science career you often need luck, but if you put in a lot of time and effort, you are sure to find it”

Maria Bernabeu and Arnau Busquets are UPF alumni of Human Biology who are leading research groups at the EMBL Barcelona and at the Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute, respectively. Both have recently received a grant from the European Research Council (ERC Starting Grant), which recognizes highly innovative projects.

Maria Bernabeu and Arnau Busquets are UPF alumni of Human Biology who are leading research groups at the EMBL Barcelona and at the Hospital del Mar Medical Research Institute (IMIM), respectively. After graduating the same year from UPF they did their PhDs in Barcelona and continued their scientific careers abroad: in the USA and in France. They have recently returned to the Catalan capital to start their independent research lines at centres located in the Barcelona Biomedical Research Park (PRBB). Arnau Busquets is developing new animal models to investigate complex cognitive processes that determine everyday decisions, while Maria Bernabeu is working on an innovative approach to the study of cerebral malaria.

Both have recently received a grant from the European Research Council (ERC Starting Grant), which recognizes highly innovative projects led by internationally renowned researchers, with the aim of helping them to set up their own teams and carry out pioneering research in Europe. We are talking to them so that they can tell us about their careers so far and the projects they are embarking on thanks to the grant.

— What aspects of the UPF bachelor’s degree in Human Biology would you highlight?

Arnau Busquets (AB): Taking the bachelor’s degree is what led me to decide to perform research into Biomedicine. During the degree, thanks to the various lecturers I had, I fell in love with research into neurosciences and so I ended up deciding to do a PhD in this field.

Maria Bernabeu (MB): Working in small groups. There were only 60 of us and that allowed us to do practicals in small groups. Also the attention we received, the constant interaction with professors doing their own research at the PRBB; this was unique to UPF, and I think it still is.

— What motivated you to start a career in research?

MB: Before starting Human Biology I hesitated between Biology and Medicine, but in the first or second year I could tell it was my passion and it was clear I wanted to do a PhD.

AB: Since I was little, I had always wanted to help people through Medicine. But in my Biology classes at high school, I had a teacher called Concepció Ferrer who told us about research into Biomedicine and I was really interested. At university I set off on a path that led me to decide to do a doctorate.

"Of Human Biology I would highlight working in small groups and the constant interaction with professors doing their own research at the PRBB; this was unique to UPF, and I think it still is"

— Maria, after the bachelor’s degree you did your doctoral degree at the ISGlobal. How would you describe this stage and what were your main findings?

MB: I was at the ISGlobal for six years, I did my master’s degree and PhD in malaria there. I worked with Plasmodium vivax, which is the kind of malaria that is most widespread around the world, both in Asia and South America it is highly prevalent; it is only in some parts of Africa. Our goal was to discover a surface antigen called Vir. Since it is impossible to culture P. vivax to study it, we used an alternative strategy and we created transgenic P. falciparum expressing proteins of P. vivax. We saw that some of these proteins interacted with receptors of human endothelial and spleen cells.

— And how did you become interested in malaria?

MB: I was interested in all infectious diseases but it just happened that at UPF we did some group work in Ecology and Microbiology on malaria and it was through doing these projects that I became interested. So, UPF had a great influence on re-steering my career!

— In your case, Arnau, you did your PhD with the Neuropharmacology group of the UPF Department of Experimental and Health Sciences (DCEXS): what was this period like for you?

AB: It was a period of constant learning. The first years of the doctoral degree aren’t easy because you are doing experiments, you build up results, but sometimes it’s not very clear what your thesis is going to end up like. I think it is rather a distance race and in the end all the pieces fit together, and, if you’re lucky, you end up publishing articles. My thesis consisted of two separate parts, first I studied in animal models the effects of cannabis on behaviour and what mechanisms in the brain produced these effects. Then we saw that an endogenous cannabis receptor that we all have in our bodies might be involved in fragile X syndrome, a disease of the autistic spectrum. We discovered that by using a drug that acts on cannabinoid receptors we could improve these different behaviours in a mouse model of the disease.

"The ERC Starting Grant is the perfect platform to launch your research career independently, we will be able to implement all of the ideas we have in the laboratory"

— Later, you left to do postdoctoral research in Seattle (USA) and Bordeaux (France): what’s your assessment of the time you spent abroad?

MB: It was really beneficial. I spent six years in Seattle and there I started working with Plasmodium falciparum, which is the most widespread species of malaria in Africa and causes the highest mortality rates. I collaborated with a lot of research groups on malaria around the world, in the US, in India, and in Malawi, in Africa. I also worked with bioengineers at the University of Washington and learned and developed the in vitro models we are using now. The opportunities to make contacts and belong to a leading research group with good funding were crucial for my career.

AB: I think sometimes there is the idea in Spain or in Catalonia that we have to go abroad because we are forced to, because there are no opportunities. But I see it slightly differently because my 5-year period in France was a very good experience that made me grow a lot. Both personally as a scientist: you learn different ways of doing things at research centres, in the laboratory, from your supervisor, and I think this is very positive. I’d describe this period as highly enriching and of great learning.

— You have recently received an ERC Starting Grant: what research are you going to conduct with this grant?

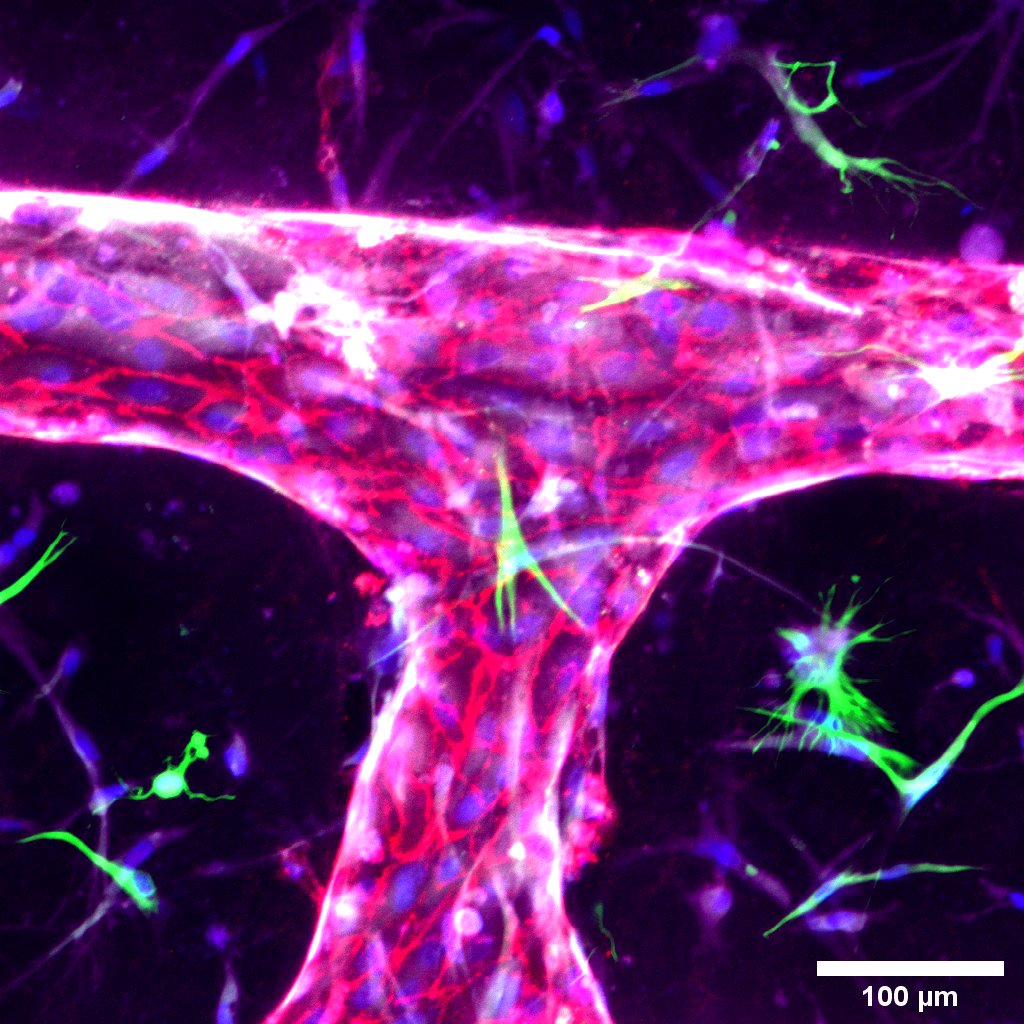

MB: This year at the EMBL we have achieved preliminary results for the ERC project. The project Mal3D-BBB studies how malaria parasites affect the blood-brain barrier, a network of blood vessels that regulates the entry of substances from the bloodstream to the brain. Cerebral malaria is a complication of malaria that occurs when blood cells infected with the parasite block the blood vessels of the brain. Usually, scientists research into this disease using models that are not ideal, in vitro experiments are too simple and animal models don’t properly reproduce the human disease. As an innovative alternative we will create three-dimensional blood vessels with exactly the same measurements, diameters and connections as are found in the blood vessels of the human brain. We will add brain cells such as astrocytes and pericytes and our goal is to create a blood-brain barrier that is impermeable to the same substances as the human one. From there, we will add malaria parasites and other cells of the immune system such as platelets and neutrophils and see how they interact with the barrier.

We have worked on this model, although covid has hindered work in the laboratory, but now we are up and running again. We are also trying to collaborate with research groups in other diseases that affect the brain and the blood-brain barrier such as Parkinson’s, or other parasites such as trypanosomes, which cause sleeping sickness. With the EMBL funding we will open these lines of research and with the ERC Grant we will focus on the blood-brain barrier and cerebral malaria.

AB: During my postdoc in France I started to use animal testing protocols that allows us to study how previous experiences are involved in making everyday decisions. In this project “Beyond classical conditioning: Hippocampal circuits in higher-order memory processes”, we will develop new animal models in mice to study how experiences that are not directly associated with other stimuli can affect our decisions. In the world of research into memory or cognition, what has been done to date in animal models is to use simple tests or study direct conditioning. To see what I mean, if I put my hand on a surface and get burnt, in the future when I see the surface I will avoid putting my hand on it. The brain somehow encodes the association between hand and surface and says to you: don’t touch because you’ll get hurt.

But, if you look at our everyday life, we constantly feel attraction to or rejection for people, places, or objects that have never been directly related to either a good or a bad experience. For example, we avoid going to a place because we might run into someone we don’t wish to see. These are indirect associations, nothing bad should happen to us there but we avoid going there because the person in question has caused us harm. This is called higher-order conditioning. The research project aims to design models to study this indirect learning, how indirect stimuli or associations may affect our decisions. I think these animal models may be far more important to study what happens in human cognition. We are now running tests with very simple animal models and we believe that a drug improves memory in a disease but we are actually seeing whether an animal prefers one object or another and I think that a slightly more complex cognitive test should get us closer to what occurs in humans.

— What does this recognition mean for you?

MB: It’s like a dream. I think it is the perfect platform to launch your research career independently. As of now, we will have no funding constraints and will be able to implement all of the ideas we have in the laboratory.

AB: When you want to start your research group in a country where research is not one of the cornerstones and where there isn’t much investment, to receive a grant from the European Union is a springboard. It really helps to create your laboratory by increasing the number of people working with you and also to have a whole range of equipment or facilities you could not enjoy without this help.

— What are your interests besides academic life?

MB: Live music is one of my interests, before covid I used to go to lots of gigs. Also running and going on excursions, in Seattle I went on loads and I hope to go again.

AB: I like doing sport and it’s great because sometimes the life of a researcher can be quite stressful. I used to play football and now I like going running, at times I’ve even motivated myself to do half-marathons and I even did the marathon in Barcelona. I also like spending time with friends and family, but now it’s a bit difficult.

— You graduated from the University together. Did you ever envisage that you would reunite years later doing research in such a familiar environment as the Faculty?

MB: We have kept in touch throughout the time he was in Bordeaux and I was in Seattle and occasionally shared grants we had applied for, the process of applying for the ERC... It was great to see that we were both awarded the ERC! I am also starting to get interested in the effects of malaria on the brain and in the future we might consider possible collaborations.

AB: We ended up being friends and, despite living abroad, with a group of friends we met up once a year and got up to date. Maria is one of those people that you might have heard nothing from for months but when you meet again it seems like you’ve not been apart. We shared the process of sending the project, and to receive the ERC was brilliant news. It makes us very happy because it is an enormous, much needed help at a time when research is not easy.

— What would you advise someone who just graduated and wants to start a career in science?

MB: To always do what they like and motivates them because a career in science and in academia is very hard and demanding; you need to feel that that’s what you do when things don’t turn out right. So, my main advice would be to devote yourself to something that makes you feel like going to work every day and putting in as many hours as are needed.

AB: There is a thing Dr. Eladi Baños said at the Human Biology graduation ceremony: “good luck but may it come to you working”. I think it really describes what a person who wants to devote themselves to research should do. Of course, you will often need luck but if you put in a lot of time and effort, you are sure to find it.