Different studies point to a relationship between language and general control skills in humans

Carried out recently by the Speech Production and Bilingualism research group at the Center for Brain and Cognition, led by Albert Costa, ICREA research professor with the Department of Information and Communication Technologies.

When people are bilingual or multilingual, and speak more than one language, they change language depending on who they are speaking to. For example, some people when they speak to their parents, they might speak Catalan, but to friends who do not speak Catalan they will change to Spanish and, to a friend visiting them, in English. So, multilingual people have to choose the language in which they wish to express their message and at the same time avoid the use of words from other languages. Surprisingly, bilingual people commit few mistakes and almost always speak in the language in which they are intending to speak. In order to do so, they have been suggested to use some kind of control mechanism.

The main goal of recent studies published by the Speech Production and Bilingualism research group (SPB) of the Center for Brain and Cognition (CBC) led by Albert Costa, ICREA research professor with the Department of Information and Communication Technologies (DTIC) at UPF, has been to find out if this control of language is specific to language or if it is similar or related to a more general control system that humans use in their everyday life.

For example, states Kalinka Timmer, first author of the studies and member of Costa’s team at the Center for Brain and Cognition (CBC) at UPF: “when we drive, we must pay attention to the cars and cyclists around us, but we must also pay attention to traffic signals, and if suddenly there’s an ambulance siren, we will focus our attention on it”. “In our study we used simple experiments to measure the general control mechanisms and the control mechanisms more specifically underlying in language”, adds Timmer.

To measure the control of the language, an experiment is used in which people name certain images, for example in three different languages (Catalan, Spanish and English), depending on the flag displayed with the image. To measure general control, participants must make decisions about colour (red or blue), size (large or small) or type (letter or number) of a particular object presented to them. Control has been seen to manifest itself in different ways. For example, in speed of response, slower when they change to a new language (or task) than when they name a new image in the same language (or task).

Finding out if this control of language is specific to the language or if it is similar or related to a more general control system that humans use in their everyday life

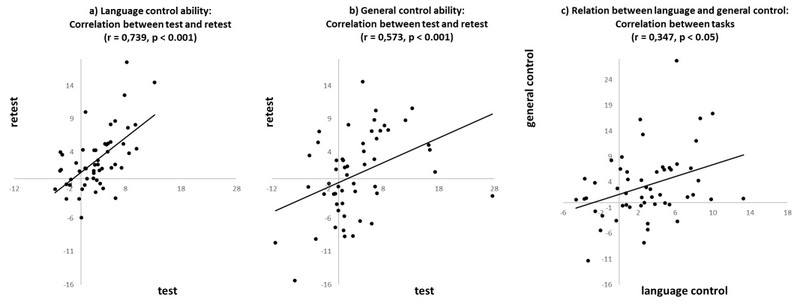

The second issue that these researchers raised was whether this measure of control was reliable and maintained over time, that is to say, if the same control capability is maintained whether evaluated today or within a week. “Otherwise, this measure was useless to us. Therefore, we did the same experiment twice with a week in between”, explains Timmer. Thus, the study revealed that, for both the control of language and for general control, this measure was quite reliable since the participants displayed similar performance on the first day and also a week later. By contrast, the researchers saw that for another type of control, more related to long-term goals, the value obtained was not reliable because it was not maintained over time, so it became clear that it was not a good measure to investigate whether the control of language is or is not related to general control.

In another study, which is currently under review, “we show that, as bilingual people are more capable of changing language, their general control also improves, again suggesting some kind of relationship between language and general control”

To investigate if language and general control were related, the researchers studied by means of correlations whether the control skills in these two domains were similar for each participant. Timmer adds, “we showed that only some of the processes underlying these two control skills are shared and that others are different. For example, during the control of language, people have to speak, which is not required for general control. But some of the mechanisms seem to overlap between language and general control”. This research is part of a larger project which attempts to explain which is the relationship between language and general control skills, and how flexible these control processes are.

In previous studies, this group of researchers showed that bilingual people have different types of language control depending on whether they are speaking their dominant language or if they are doing so in a second, non-dominant language. In another study, which is currently under review, “we show that, to the extent that bilinguals are more able to change language, it also improves their general control, again suggesting some relationship between language and general control”, concludes Timmer.

Refered works:

Timmer, K., Calabria, M., Branzi, F. M., Baus, C., & Costa, A. (2018), “On the reliability of switching costs across time and domains”, Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1032. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01032

Timmer, K., Christoffels, I. K., & Costa, A. (2018), “On the flexibility of bilingual language control: The effect of language context”, Bilingualism: Language and Cognition. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728918000329