The interface, a concept to rethink the world in the wake of the pandemic

A new UPF study analyses computer games as if they were an interface, studying all the actors in the game and their interactions. The authors affirm that this methodology can be applied to transform the relationships and processes of many activities and structures of the human being.

As part of an international project, a team from UPF analysed adolescents’ experience of online games as if they were an interface, with the aim of discovering the use that young people make of the media and how they learn from them. This approach allows discovering all the different types of actors that participate in online games and the relationships that exist between them. The results of the research were published in the journal First Monday.

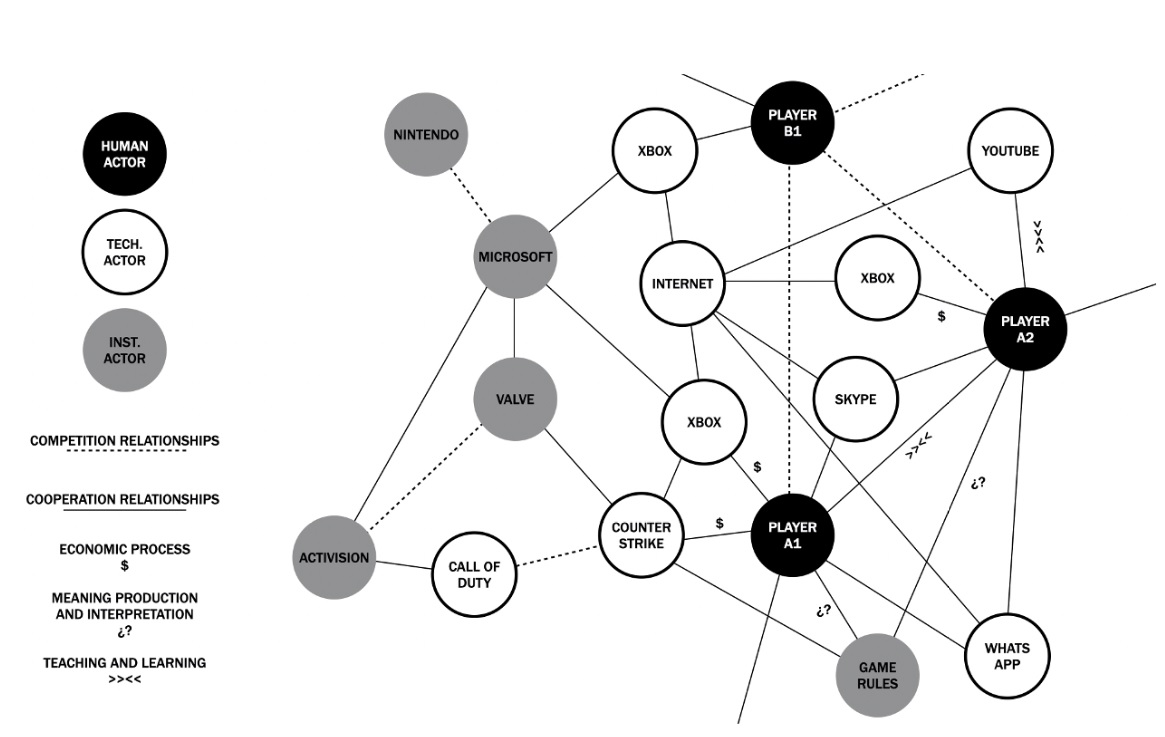

“In the 19th century, the term interface was coined to define something that separated two environments, like a membrane”, explains Carlos Scolari, a professor at the UPF Department of Communication and first author of the article. “Here, beyond considering only the graphical user interface (GUI) such as the console, computer or mobile, we study all actors, both human and technological, and the relationships that exist between them”.

Thus, one of the results of the study was the creation of a map of the actors, the relationships and processes of the online video game interface, paying special attention to the tensions and critical issues that arise between them. This methodology allows discovering the problems and advantages of all processes, revealing patterns, behaviours or situations that could otherwise not be seen.

The study involved adolescents aged between 12 and 18 years from 8 countries (Australia, Colombia, Finland, Italy, Portugal, Spain, United Kingdom and Uruguay). With them, 1,633 questionnaires, 58 participatory workshops and 311 interviews were carried out, collecting data on the human, institutional and technological actors that participated in the games.

The study involved adolescents aged between 12 and 18 years from 8 countries (Australia, Colombia, Finland, Italy, Portugal, Spain, United Kingdom and Uruguay). With them, 1,633 questionnaires, 58 participatory workshops and 311 interviews were carried out, collecting data on the human, institutional and technological actors that participated in the games.

The study found that game environments are highly complex. Communication between young people consisted of various layers and used different tools (through the game itself or using other platforms such as Skype and WhatsApp that show a high degree of online coordination to do things). One of the participants, Alex, a 13-year-old Spanish boy, explains one detail of this interaction: “We are connected throughout the game, we organize ourselves and if we need help with something or at any particular point, we tell [those who are not connected] to come and connect quickly and that’s it”.

Another technological actor present in games is YouTube as a platform to share knowledge to solve problems audiovisually, or to find shortcuts and errors in software that allow players to progress in the game.

Currently Scolari and one of the authors of the article, professor Fernanda Pires of the UAB, are also working on “Project PLATCOM: Communication platforms, workforce and informal learning”, funded by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation. This project aims to analyse all the people who work for tourism (AirBnB), transport (Uber, BlaBlaCar) or delivery (Uber Eats, Glovo, etc.) platforms using the interface methodology. “We are interested in studying last mile actors, such as the riders from delivery companies or AirBnB cleaning workers (most are women). We have found that between the platforms and the workers there are intermediary companies that are very important, though sometimes rather unknown actors, in the universe of what is known as the new ‘platform capitalism’”.

The researchers aim to apply the interface concept to detect tensions or conflicts between actors, even in very different phenomena or activities, from the school classroom to major industry, a political party or a country’s health system.

The researchers aim to apply the interface concept to detect tensions or conflicts between actors, even in very different phenomena or activities, from the school classroom to major industry, a political party or a country’s health system. The interface can always be scalable to whatever is desired and will allow redesigning and transforming those activities to make them more efficient. “If we identify these problems quickly”, Scolari comments, “later on we will be able to use other methodologies, such as Design Thinking, in a more effective way since they would be focused only on problematic aspects”.

The researchers advocate a total change in the way relationships take place in the most basic and fundamental structures of our society. The challenges that we must face in the 21st century require rethinking education, health, political participation, to give just a few examples, in order to respond to these new challenges.

“Let’s look at the example of education”, he explains, “a structure created from an 18th-century model that responded to the needs of that time, but not those of the post-industrial era. Right now, the pandemic has manifested the shortcomings, not so much of the students and their families, but of the institution itself, in adapting to distance education. A vision that incorporates the relationships between all the human, technological and institutional actors in education will allow us to pinpoint the failures and tensions in the system and be able, at the same time, to transform them”.